by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, Money Metals:

While 99% of the media keeps staring at official data by the Chinese central bank (PBoC)—misleadingly stating it added 5 tonnes of gold in November following a supposed six-month pause—the PBoC’s “unreported” purchases in London accounted for a stunning 60 tonnes in September and another 55 tonnes in October.

And while cross-border trade statistics from the U.K. for November have yet to released, I foresee another purchase of a similar magnitude.

Chinese authorities see a greater role for gold in the future international monetary system, or they wouldn’t continue buying such extraordinary amounts of gold. Via London alone, the PBoC has stockpiled 1,000 tonnes of gold since Russia’s foreign exchange assets were “frozen” by the West early 2022.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

London Exports to China Are a Proxy for PBoC Buying

Since July this year, I have been writing that a large share of China’s gold imports into the domestic market is not bought by the private sector. We can conclude that the bars exported from the U.K. to China are secretly destined for the PBoC.

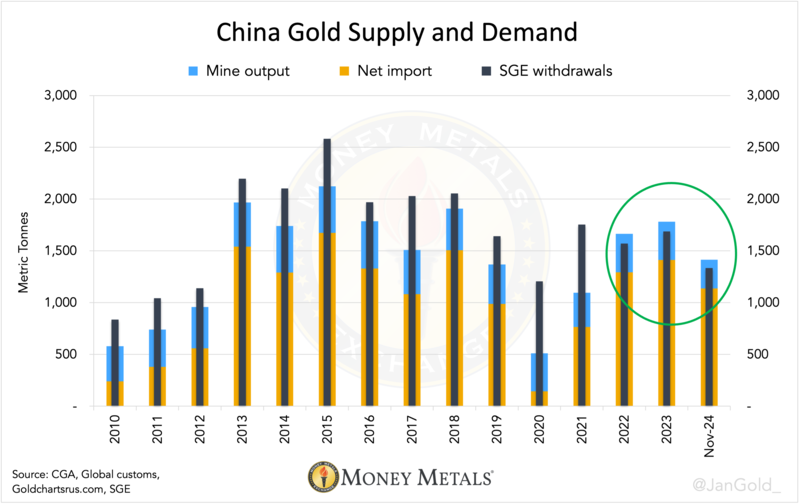

Initially, I based my analysis on a pronounced surplus in the Chinese domestic gold market—resulting from supply (mine, recycled gold, and imports) outstripping demand. The most conceivable explanation for this surplus is that the central bank of China is behind large gold imports.

Chart 1. From 2022 until November 2025 there is a surplus in the Chinese gold market, because import and domestically mined gold was more than SGE withdrawals.

My findings became more evident when in September the premium on the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE) turned negative, but Chinese gross imports accounted for a sturdy 95 tonnes for the month.

It makes no economic sense for any bullion bank to buy gold abroad and sell at a loss at the SGE. The 60 tonnes (in 400-ounce bars) exported in September from the London Bullion Market to China went to the vaults of the PBoC in Beijing, I therefore concluded.

The PBoC Keeps Up the Pace, Buying 55 Tonnes in October

I noted the following in my last article:

…we can see that in October, the SGE was trading at a discount while imports reached 95 tonnes, which was the same as in the prior month. I strongly suspect the PBoC was secretly buying gold in London again.

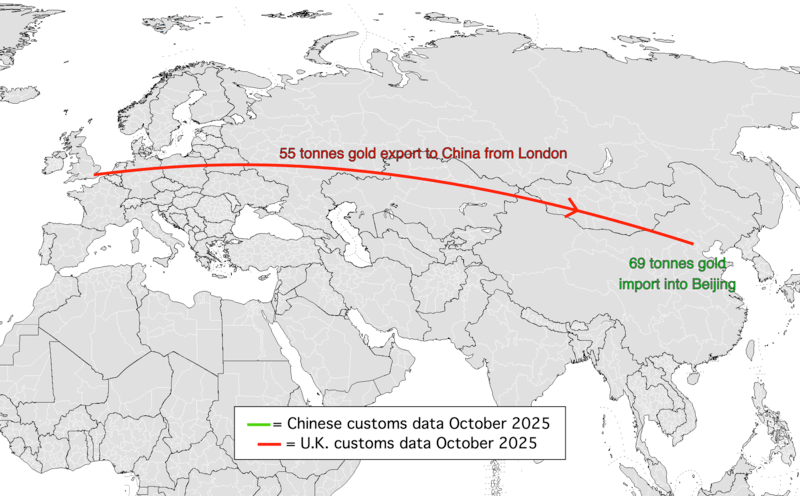

Recent data by Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (HMRC)—Britain’s tax, payments and customs authority—reveal 55 tonnes were indeed dispatched from the London region to China in October.

Graph 2. Courtesy of Wikimedia for the map.

Meanwhile, it’s likely the PBoC also bought gold elsewhere. Total imports into the Beijing region accounted for 69 tonnes in October, as per General Administration of Customs People’s Republic of China. That’s 14 tonnes more than what was shipped from London.

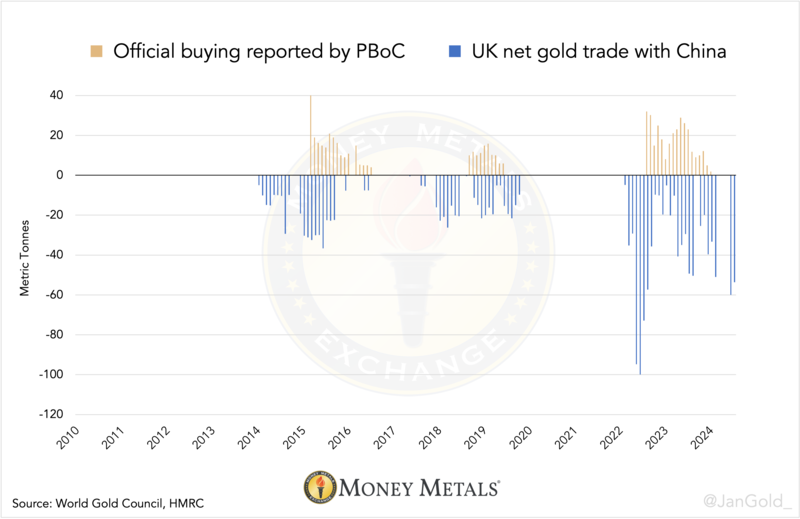

An illustration I shared previously is a chart of the PBoC’s publicly disclosed gold purchases versus U.K. gold exports to China. The chart shows both are loosely correlated “although the PBoC usually takes up to a year to publicly report its acquisitions and keeps about 65% of it hidden” (quote from my article from November 26, 2025).

Chart 3. The PBoC’s publicly disclosed gold purchases versus U.K. gold exports to China that serve as a proxy for covert buying by the Chinese central bank.

Only two months after September (when the PBoC covertly resumed buying in London), it revealed to the world it bought a mere 5 tonnes in November. Even this fraction of the truth boosted sentiment in the gold market. Go figure.

The Chinese central bank is currently buying at least ten times more gold than what you read in the newspaper, and yet markets got excited based on mere breadcrumbs!

Goldman Sachs Writes on PBoC Gold Buying in London

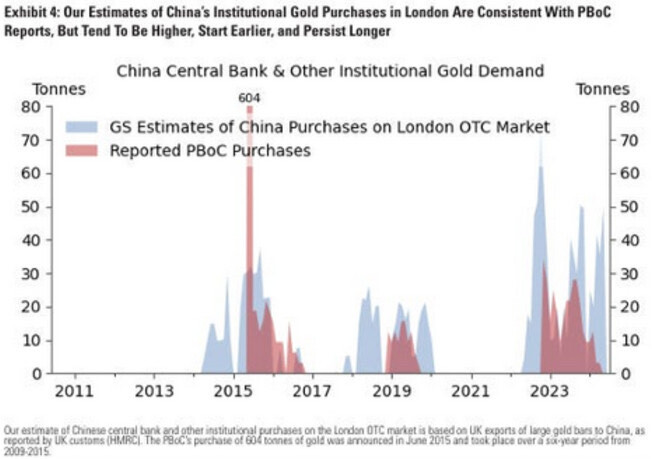

Meanwhile, my research is gaining traction as it was picked up by Goldman Sachs (GS). Below you can see a chart by GS displaying what I first demonstrated in July, but with a different design.

Chart 4. Courtesy of Goldman Sachs.

At the bottom it reads “our estimate of Chinese central bank … purchases on the London OTC market is based on UK exports of large bars to China, as reported by UK customs (HMRC).” (Parroting my own conclusion.) Eventually other media will start writing about these huge purchases as well.

For me, this topic reminds me of my early work analyzing SGE withdrawals. In 2013, I began spotlighting the volumes of gold withdrawn from SGE vaults, documenting why that is a proxy for Chinese wholesale demand. By implication, gold demand in China at the time was twice what consultancy firms stated. A few years later, nobody argued about the meaning of SGE withdrawals anymore.