by Brian Shilhavy, Health Impact News:

It was reported earlier this week that another Catholic Diocese in California has filed for bankruptcy due to recent surges in lawsuits filed against pedophile priests during the past few years, which has caused attendance and support for Catholic Churches to plummet.

Fresno Diocese to file for bankruptcy amid surge in clergy abuse claims

The bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Fresno says the diocese plans to file for bankruptcy in a matter of months.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

That’s following what it calls a “Surge” in clergy sexual abuse claims.

The California sexual abuse and Cover-up Accountability Act helped bring the number of credible accusations within the Diocese of Fresno to 154 cases, dating back decades.

The bishop says the only way to resolve every claim fairly and compassionately is to file for bankruptcy.

“When I hear how many lives were affected by clergy sexual abuse, my heart truly breaks,” said Bishop Joseph V. Brennan with the Diocese of Fresno.

“Victims of abuse endure a lifetime of pain, and we as Catholics must commit to a lifetime of atonement,” said Brennan.

The Fresno Diocese is not the first one to file for bankruptcy due to backlashes from pedophile priests, but follows the Diocese of Sacramento, the Archdiocese of San Francisco, the Archdiocese of Oakland, and the Diocese of Santa Rosa.

While Catholic Churches across the U.S. have been going bankrupt in recent years as more and more cases are filed by the victims of Catholic pedophile priests who prey on children, that process accelerated in California after a 2019 legislative bill was passed that opened a three-year “look-back window” that would allow survivors of childhood sexual abuse to file suits based on old claims that would normally have fallen outside the statute of limitations.

When the window closed in 2022, more than 2,000 individuals around the state had filed cases against the Catholic Church.

Many of the victims who are now adults and were formerly abused by Catholic clergy, claim that filing bankruptcy by these dioceses is a cop out to avoid paying out settlements to the victims.

But the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, also known as SNAP, says filing for bankruptcy could do more harm to the victims.

“If the catholic church is going to hold itself out there as a moral beacon for a fallen world, then I think they have to act like a moral beacon. And I frankly think these bankruptcies are immoral,” said Melanie Sakoda, the SNAP Survivor Support Director.

She says if the church files, this could be a legal tactic to protect itself.

“#1, these children will never have a chance to be compensated for their injuries, and #2, It’s sad for the people in the parishes too, because they will never…that information about who these abusers are may never see public light,” said Sakoda.

“There’s no way that the church can weed out all the abusers, and churches are attractive to predators, so when you…If you take your children to church, pay attention to changes in behavior. Don’t just assume that because it’s the church that, it’s 100% safe.” (Source.)

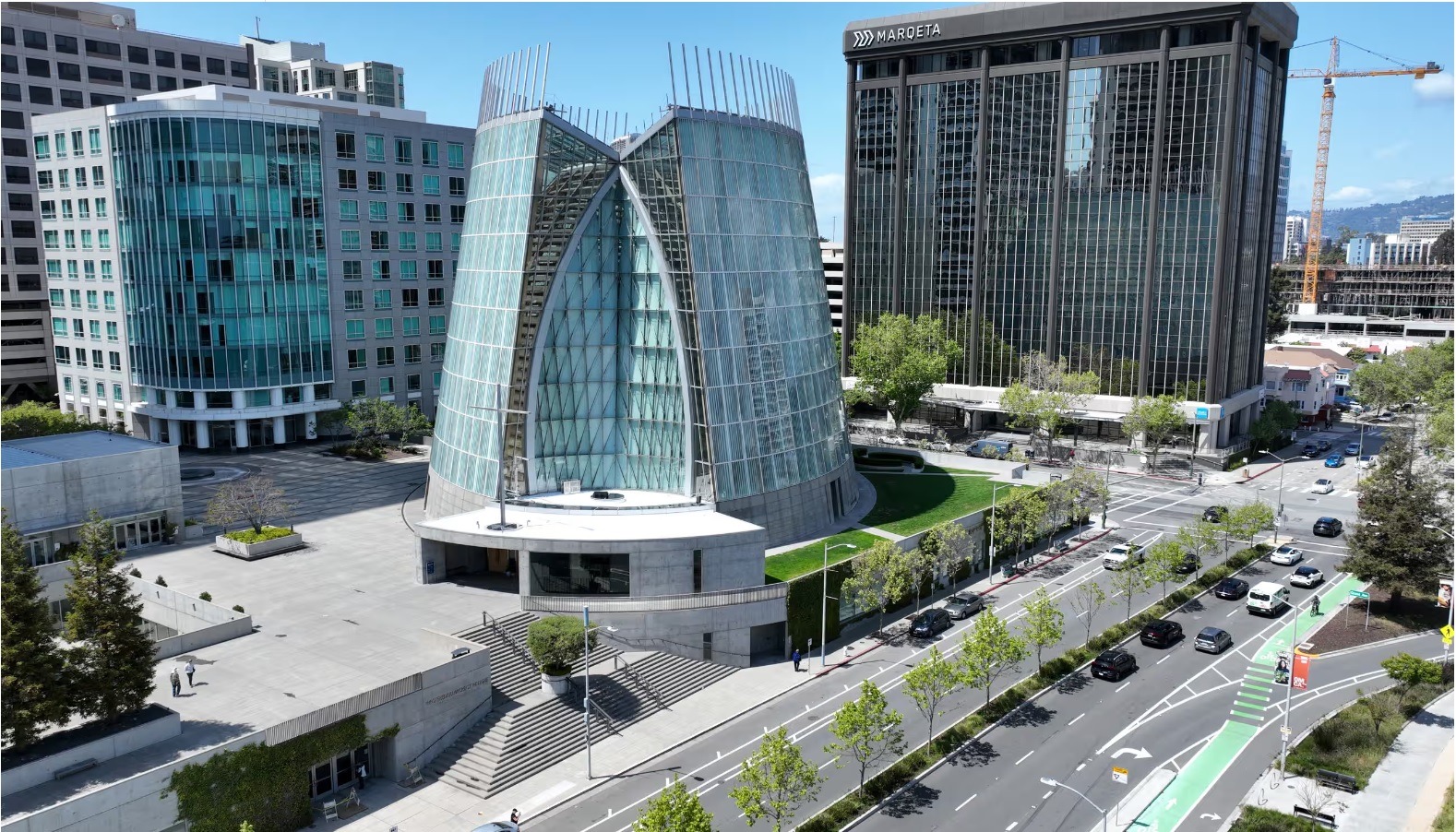

The Cathedral of Christ the Light in Oakland, California. Photograph: MediaNews Group/East Bay Times/Getty Images. Source.

Robin Buller, a reporter who lives in Oakland and published an excellent investigative report in November of 2023 for The Guardian, revealed that these dioceses that declare bankruptcy do not mean that the churches don’t have money, as she referenced a Catholic Church in Oakland that just built a $200 million cathedral recently.

Catholic dioceses are declaring bankruptcy. Abuse survivors say it’s a ‘way to silence’ them

One by one, various arms of the Catholic church across California have declared bankruptcy, citing an inability to pay damages from large numbers of sexual abuse lawsuits.

The dioceses of Santa Rosa and Oakland filed in the spring. The archdiocese of San Francisco followed suit in August, and the diocese of San Diego has shared its plan to do the same in November.

The lawsuits come at a time when Catholicism in California is growing – fueled in large part by immigration from Latin America and Asia – while other parts of the US, including former Catholic hubs in the north-east, are seeing their numbers dwindle.

Church bankruptcy declarations are not unprecedented. From Portland to Milwaukee and from Helena to Rochester, dioceses have been declaring – and emerging from – chapter 11 bankruptcy for nearly two decades.

And it isn’t only the Catholic church taking these steps. The Boy Scouts of America likewise sought protections amid thousands of sexual abuse allegations in 2020.

The flood of California suits came after 2019 legislation opened a three-year “look-back window” that would allow survivors of childhood sexual abuse to file suits based on old claims that would normally have fallen outside the statute of limitations.

When the window closed last December, more than 2,000 individuals around the state had filed cases against the Catholic church; 330 accusers have sued the Oakland diocese alone.

“No one really expected this huge number [of abuse cases] to come in at this last month,” said Maureen Day, a sociologist and associate professor of religion and society at the Franciscan School of Theology.

“It suddenly became a much larger financial hardship for many dioceses.”

But declaring chapter 11 does not mean that the church is broke, said Marie Reilly, professor of law at Penn State University.

Rather, it is a legal strategy undertaken by corporations that say they don’t have the funds to pay a high number of individual settlements.

Known as “reorganization”, these bankruptcy protections let the church avoid undertaking dozens, if not hundreds or thousands, of individual costly trials by grouping them into one settlement.

“It will look like more of an administrative process,” said Reilly, who specializes in bankruptcy law and also created a database that tracks diocesan bankruptcies.

To abuse survivors, the proceedings feel like a cop-out. “It’s just another way to silence us,” says Dan McNevin, who leads the Oakland chapter of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (Snap) support group.

Unlike trials, bankruptcy proceedings do not involve a discovery process, meaning key pieces of information about what church leaders knew may never be revealed.

McNevin knows how meaningful those revelations can be.

As a child, he was an altar boy at his local parish in Fremont, south of Oakland, where he says he was groomed and abused by his priest.

In 2003, following California’s first look-back window, he brought a suit against the diocese of Oakland, claiming it had knowingly shuffled his abuser from place to place to mask his crimes.

The diocese initially denied those claims, but during the trial, documents unearthed during discovery revealed that Father James Clark had been convicted of sexual abuse years before he arrived in Fremont.

“When we discovered that he had been arrested, my case was made,” said McNevin.

“It probably helped settle 60 cases.” But those cases were settled individually, not collectively, as they would be in bankruptcy proceedings – a critical difference to McNevin.

“They’re going to try to slice and dice the survivors into categories,” he said.

“How do you contemplate making those kinds of stark arbitrary decisions when every human being is different?”

Melanie Sakoda, survivor support coordinator at Snap, says the removal of the discovery process results in victim retraumatization.

“What they’re really looking for is information,” she said.

Read More @ HealthImpactNews.com