by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, Gainesville Coins:

Because central banks are the root of the modern money tree, they can use entries in their gold revaluation accounts to turn into capital, pay for expenses, or transfer it to their respective Treasuries. In addition, gold revaluation accounts can be used to cancel government bonds held on central bank balance sheets to lower the public debt.

Multiple large central banks are currently operating at a loss while public debt levels are elevated. In this article we will examine how central banks’ gold revaluation accounts can offer solace in these challenging financial environments. Central banks’ accounting rules are but fictional obstacles, as these are self-imposed and can be discarded.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

Introduction

My most recent article on gold revaluation accounts (GRAs) covered a statement from Joachim Wuermeling, member of the Executive Board of the German central bank (Bundesbank, or “Buba”). In March 2023, Wuermeling said the Bundesbank’s €180 billion GRA is part of his central bank’s own funds (capital). Regarding losses the Bundesbank is suffering from, and the expectation that in subsequent years its capital will be wiped out, Wuermeling commented:

What is also of interest is the revaluation accounts. … The most important revaluation item of course is … gold. In fact, the value is about €180 billion euros above the cost of purchasing it, … and it’s part of the considerable own funds of Bundesbank, underlining the soundness [of our balance sheet]. So, in fact, it’s on firm ground, the balance sheet of Deutsche Bundesbank, and this certainly makes it easier for us to bare losses over a certain period of time.

Wuermeling’s statement highlights Buba’s GRA as its solvency backstop. Previous to this statement Buba suggested that the prevailing accounting rules of the European System of Central Banks prohibit GRAs from being used for anything other than offsetting unrealized losses in gold. Now, by speculating to use their GRA to offset general losses, the Germans can’t be bothered by the rules, whatever they are.

Central Bank Balance Sheets and the Gold Revaluation Account

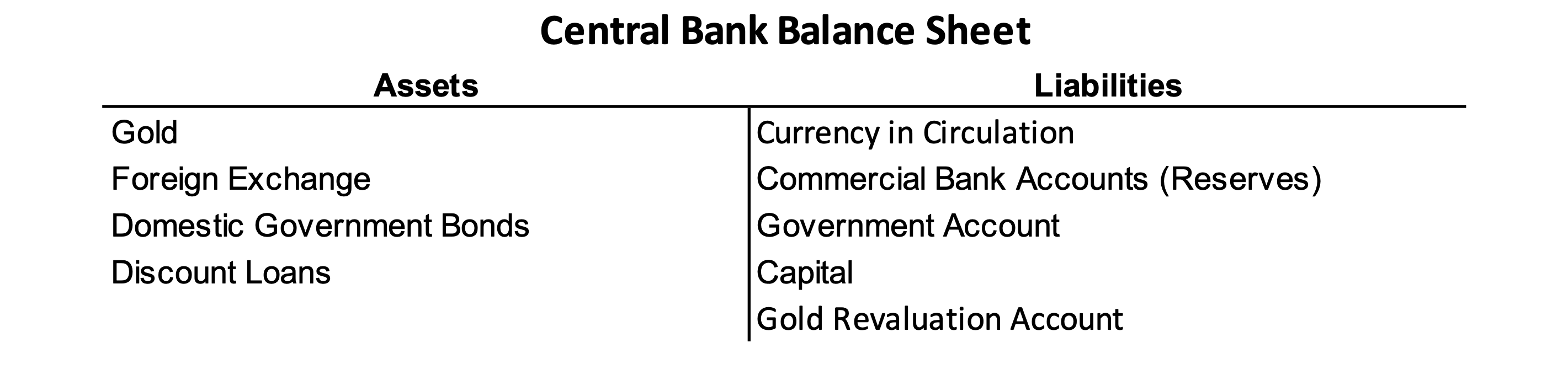

A GRA is an accounting item on the liability side of a balance sheet that records unrealized gains of gold assets. For those central banks that mark to market the gold on their balance sheet, not only the asset side increases when the price of gold rises, the liability side increases too. Let’s have a look at an example central bank balance sheet and see how gold fits in.

Relevant to our present discussion: Currency in circulation are coins and notes. Reserves are currency in book-entry form and represent funds that commercial banks hold at their central bank, used to clear interbank payments, or to be converted into physical currency. Currency and Reserves form a country’s monetary base (base money). Next to commercial banks, the national Treasury has an account at the central bank, often referred to as the Government Account. Capital is the central bank’s financial buffer, swelling when profits are made, and shrinking when losses accrue. Gold reflects the value of the central bank’s gold assets. Domestic Government Bonds are bought by the central bank in the open market to conduct monetary policy (or finance the government). We will pretend the central bank has two types of customers: the government and commercial banks. Finally, Capital plus the GRA makes up the central bank’s Equity.

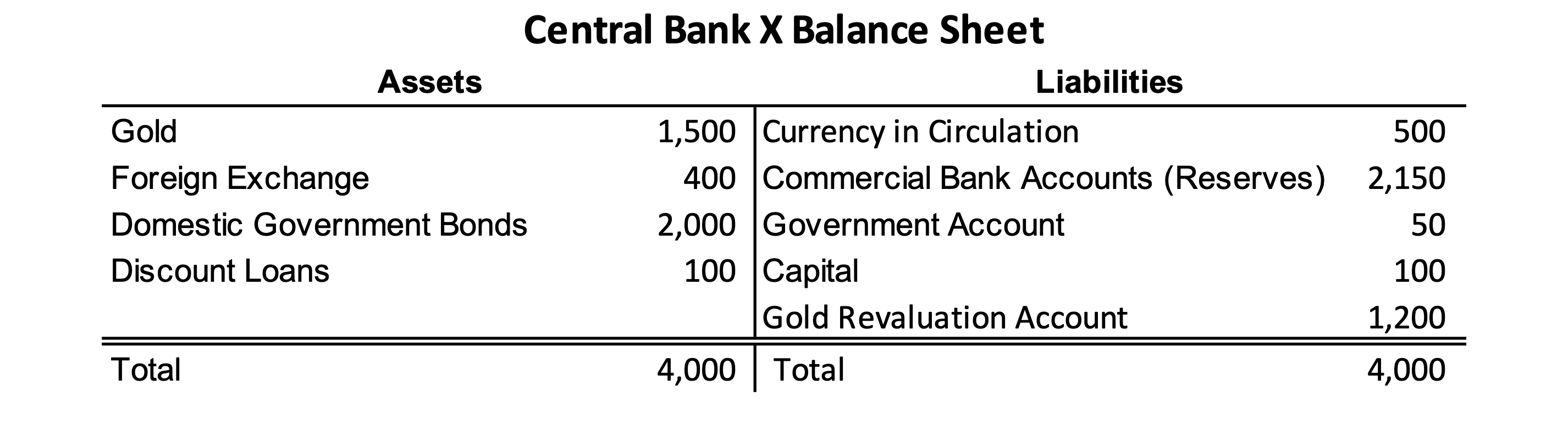

Regarding the GRA, suppose the central bank of country X (CBX) buys 300,000 troy ounces of gold for $1,000 local dollars per ounce, at a total cost of $300 million. In thirty years’ time the gold price rises by 400% to $5,000 dollars an ounce. The value of CBX’s gold has gone up to $1,500 million, and its unrealized gains to $1,200 million ($1,500 million minus $300 million). Reiterating, a GRA keeps track of the unrealized gains on gold assets—in our example at $1,200 million.

GRA = present gold value – historic gold purchasing cost

Central bankers will typically say the GRA is used for cushioning downturns in the value of their gold (page 26). If the gold price declines, the GRA shrinks (as well as the value of gold assets), and the central bank doesn’t have to record a loss on its gold. But, as we will see later on, GRAs can be deployed for a variety of alternative uses.

To wrap our heads around the applications for GRAs, we need to understand the balance sheets of central banks, but also their cash flows and ability to create (“print”) base money. Because central banks can create money, they can also turn GRAs into money. The following is highly simplified.

Central Bank Cash Flows

In the past, commercial banks could redeem base money for a central bank’s gold assets at a fixed parity. The monetary base represented physical gold. Until 1971, that is, when the last remnants of the gold standard were relinquished. Since then, Commercial Bank Accounts—but also the Government Account and Capital of central banks—are just numbers. Next, we will explore how these numbers flow from one part of their balance sheet to another to improve our understanding of how central banks function.

By example, CBX earns $10 million dollars in interest on Domestic Government Bonds it holds as assets. To collect money (income) from the Treasury, CBX debits the Government Account and credits its Capital. In turn, CBX has to pay $10 million in interest on Commercial Bank Accounts—to set monetary policy central banks pay interest on their reserve liabilities. This interest (expense) is disbursed by CBX through debiting its Capital and crediting Commercial Bank Accounts. All else equal, in this example CBX breaks even on its income and expenses.

If CBX’s income transcends its expenses, it can choose to allocate this profit by increasing its Capital, or transfer funds to its largest shareholder through increasing the Government Account. In case expenses are higher than income, CBX has to tap its Capital.

From these examples of cash flows, and what we have discussed prior, we conclude a central bank’s Equity comprises of realized gains (Capital) and unrealized gains (GRA).

How Central Banks Can Turn Gold Revaluation Accounts into Money

In the world of accounting central banks can turn unrealized gains (GRA) into realized gains (Capital), because it is their bookkeeping that determines what is base money. Technically, there is no barrier for central banks to move entries from their GRA to their Capital or use it to pay for expenses. Once the funds end up in Commercial Bank Accounts, they have increased base money.

In one of my previous articles on this subject I reported how the central bank of Curaçao and Saint Martin (CBCS) sold and immediately bought back some of its gold assets in 2021. Through these transactions CBCS was able to circumvent the accounting rules and move entries from its GRA to its Capital to cover general losses.

Read More @ GainesvilleCoins.com