by Rhoda Wilson, Expose News:

As damning evidence continues to emerge of the harms of lockdown for children, Joanna Williams in the Telegraph highlights recent research finding rising numbers with eating disorders and social anxiety, and who are self-harming and dropping out of school. Here’s an excerpt.

The fact our young suffered the effects of lockdown in many more ways than we could ever have predicted has left parents, schools and the healthcare system reeling in the virus’s wake. But today, little is being done.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

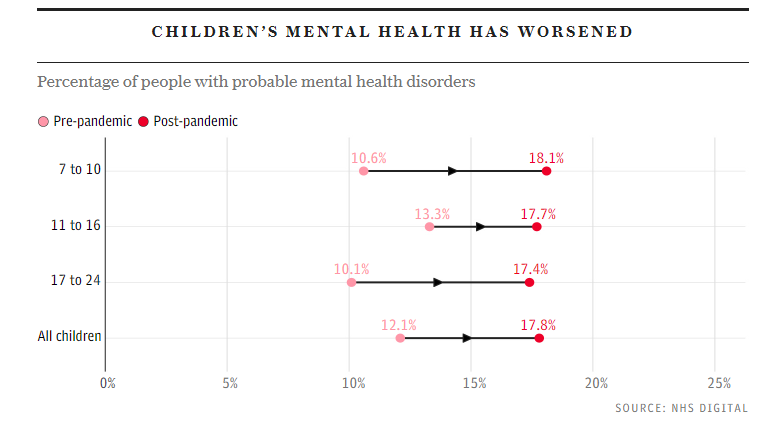

Over the pandemic’s course, the number of youngsters seeking help for mental health problems soared, jumping from an estimated 12.1% of children in 2017 to 17.8% in 2022. The youngest children – those aged between seven and 10 – saw the biggest increase. But adolescent mental health issues have also become more prevalent, with new research this week showing that lockdowns fuelled a staggering 42% rise in eating disorders among teenagers – the sharpest rise being in girls aged between 13 and 16 – and led to a similar increase in incidents of self-harm.

The lead author of the latest study suggests that social isolation, anxiety, disruption in education and over-exposure to negative social media influences left many children feeling they had lost control over their lives, and that this could have contributed to the development of eating disorders. Hospital admissions because of eating disorders had their sharpest annual increase in the year after the pandemic, rising from 5,950 among under-18s to 7,767.

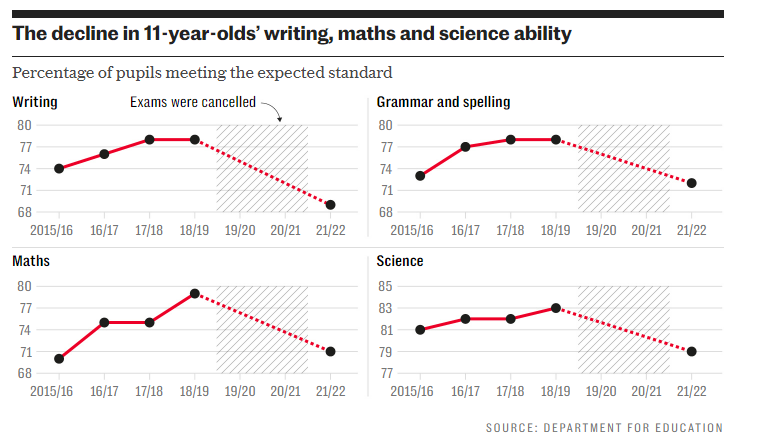

School closures had a devastating impact on education. Pupils starting in reception in 2019 spent, on average, 85 days out of class. Some, especially those placed in ‘bubbles’ where entire year groups were sent home if just one pupil tested positive, missed far more. As a result, the proportion of pupils meeting literacy and numeracy benchmarks at the end of primary school fell from 65% in 2018-19 to 59% in 2021-22.

Some children suffered far more from school closures than others. While some received a full timetable of interactive online lessons, many did not.

The difference in performance between those from disadvantaged backgrounds and their better-off classmates widened significantly between 2020 and 2022 – reversing a trend that had seen the educational attainment gap between rich and poor shrink over the previous decade.

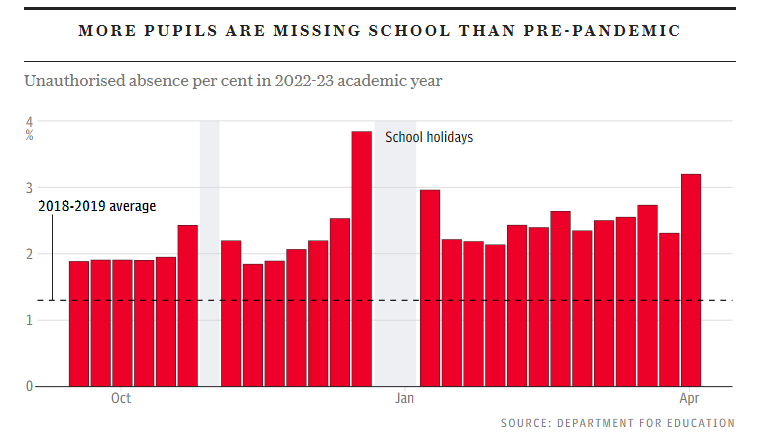

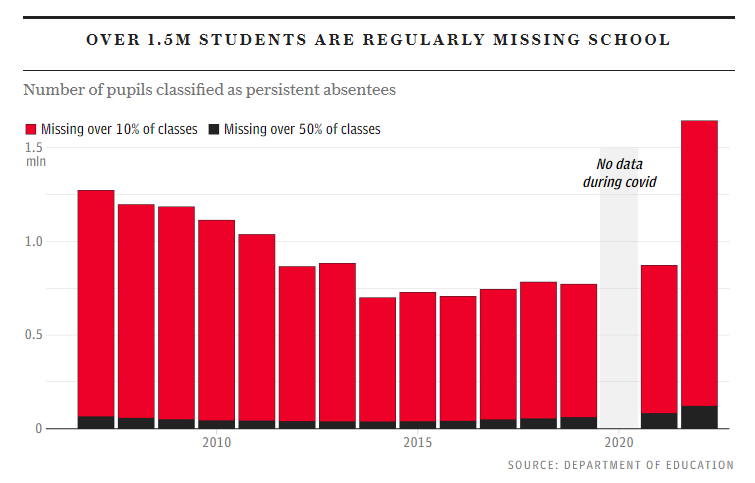

Once schools reopened, many thousands of children failed to turn up. Last year, pupil absences stood at double pre-pandemic levels, with around 1.5 million children missing over 10% of timetabled classes. The number of severely absent children has risen by more than 50% in a year. Truancy is far higher in more socially deprived communities.

Despite this damning weight of evidence, the national Covid Inquiry has – so far – shown little interest in acknowledging lockdown’s impact on children. Or interrogating why this situation was allowed to occur.

The week former chancellor George Osborne revealed what was really at stake with scattergun lockdown policies when he gave evidence at the inquiry earlier this week. Governments have to weigh “life expectancy” against sacrificing “the educational opportunities of an eight year-old” he declared. While we are yet to learn exactly how the “weighing up” took place, the conclusion of such deliberations has long been clear.