by Jan Nieuwenhuijs, Activist Post:

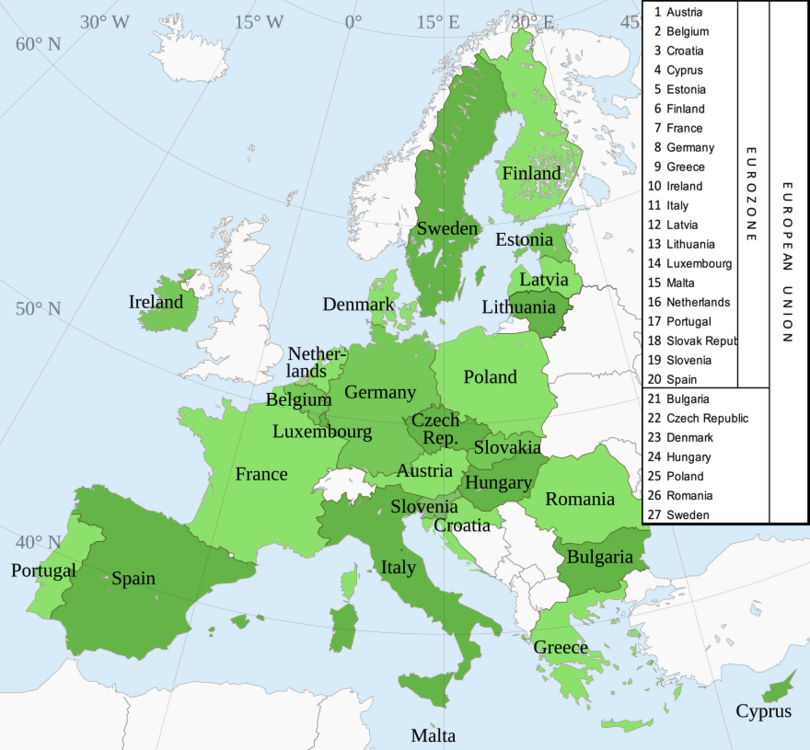

Countries outside the eurozone but inside the European Union, i.e., those that one day might join the eurozone—like Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, are positioning for a new gold standard.

To prepare for a monetary system based on gold, they are buying gold to equalize their reserves to the eurozone average. This balancing of gold reserves in Europe is a key topic I have written about extensively.

And now, additional evidence of these plans has come out, this time from Konrad Raczkowski, former Minister of Finance of Poland.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

Raczkowski recently argued official gold reserves in Europe must be evenly distributed relative to GDP, which “in the near future … will be the new gold standard.” His statement adds to a vast body of proof regarding Europe’s preparations for a gold standard.

As the United States, issuer of the world reserve currency, has arrived at a critical phase in its debt spiral and as geopolitical tensions keep mounting, it’s of paramount importance we evaluate what gold’s role will be in the international monetary system moving forward.

Gold Is Central Banks’ Plan B

Most of the largest central banks have a “Plan B” when their paper policy goes haywire, and this backup plan is, to a certain extent, coordinated between them. The first seeds of Plan B were planted by European central bankers and politicians in the 1970s. Only the U.S., together with some of its most obedient vassal states, has been unwilling to cooperate.

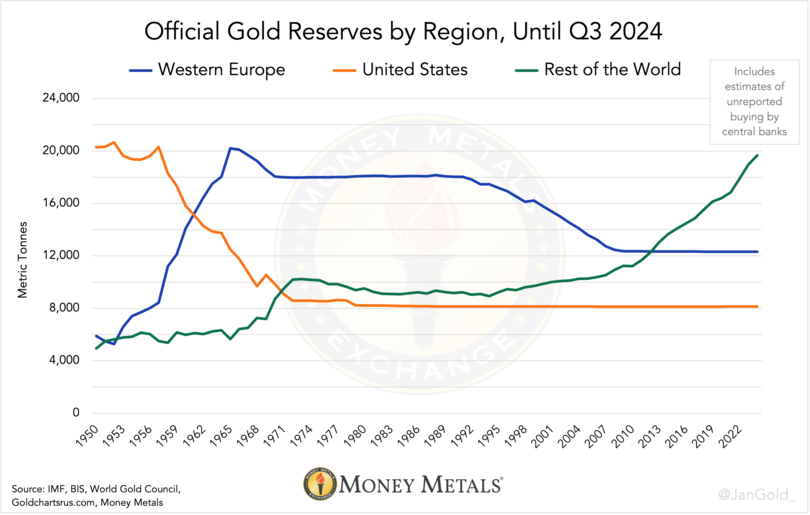

Plan B, of course, is gold, owned by virtually every monetary authority on this planet and bought by non-Western central banks in record amounts in the past years in response to dollar weaponization and debasement (see chart 1 below). A marked change in the international monetary order awaits us.

Why European Nations Want to Evenly Spread Gold Reserves

During the demise of Bretton Woods, it was clear that several European countries wanted to switch to a gold standard. They couldn’t pull it off at the time, partly because the United States was using its military strength to block such efforts. Another reason was that the world’s monetary gold was unevenly distributed at the time. Most metallic reserves were held in Western Europe1.

Chart 1. Official gold reserves are more dispersed across the world than ever.

When the world switches to a new monetary system, that new system will thrive best if all countries have an equal amount (proportionally) of the new monetary unit. In the 19th century, as most countries went on the classic gold standard, gold demand increased, which pushed up the price of gold and led to deflation (gold was the unit of account).

The more skewed the current distribution of official gold reserves, the less smooth a transition towards an international monetary system based on gold.

In the early 1990s, European central banks began selling gold reserves. The central bank of the Netherlands (DNB), for example, sold 400 tonnes in 1992. The gold was sold through the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), off the market, to the Chinese central bank (PBoC). This was the first step towards a more balanced distribution of gold.

As selling by Europe went on, the gold market got worried that uncoordinated sales were destabilizing the market and driving the price down. As a result, in 1999, at the annual IMF meeting in Washington DC, fifteen European central banks signed an agreement to coordinate their sales2. This agreement would become known as the Central Bank Gold Agreements (CBGA).

In the CBGA, they stated that “gold will remain an important element of global monetary reserves. The collective sales will be limited to 2,000 tonnes over the next five years, about 400 tonnes per year.” The signatories also announced that their lending would not increase over the same five-year period (they had 2,119 tonnes on lease in 1999).

The announcements prompted an upward reversal in the gold price—much of the uncertainty surrounding the scale of gold selling by the official sector had been removed. CBGA was repeatedly extended, up until 2014, although most of the selling stopped after 2008.

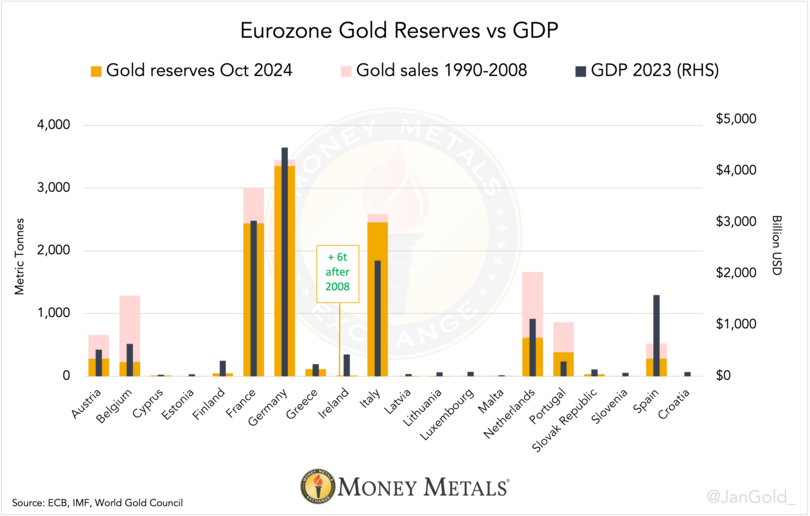

CBGA seemed like an agreement for coordinated gold sales. But for those paying close attention, it was obviously meant to equalize gold reserves among countries relative to GDP. Only medium-sized economies in Europe sold heavily, while large economies sold very little.

Additionally, of the small countries, Cyprus, Estonia, and Lithuania, didn’t sell an ounce of gold during the “concerted programme of sales.” And Ireland even added half a tonne in 2007 and continued buying after 2008.

Chart 2. Eurozone Gold Reserves vs GDP. Source: ECB, IMF, World Gold Council, Money Metals Exchange.

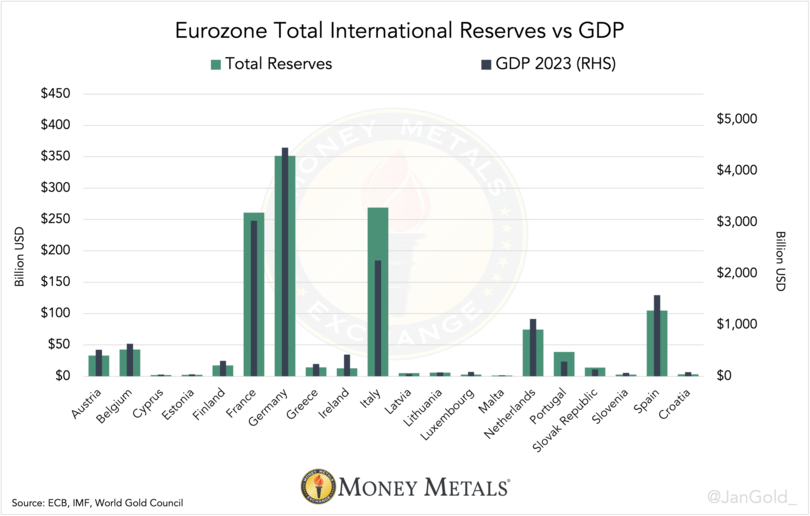

Spain is an outlier in chart 2, although it has more foreign exchange than the other countries. Total reserves (gold and foreign exchange) in the eurozone are more accurately spread than just gold.

Chart 3. Eurozone Total International Reserves vs GDP. Source: ECB, IMF, World Gold Council, Money Metals Exchange.

Within the eurozone, some central banks (that hold too little or too much gold on a relative basis) might cooperate by swapping foreign exchange for gold before gold is revalued. That way, they enjoy the same advantages in their gold revaluation accounts, which can be used to offset bad debt on their balance sheets. This would be the crown on the monetary reset.