by Brian Shilhavy, Health Impact News:

Today many Americans will commemorate the signing of the “Declaration of Independence” on this date in 1776, where many Christians and their Pastors will proudly claim that this document provided “freedom and justice for all” under the new nation, The United States of America.

And while almost everyone would probably agree that “freedom and justice for all” is not something most Americans enjoy today, they will claim that it was once the hallmark of our country, as espoused by the “Founding Fathers”, and that we need to return to those days to truly have “freedom” today.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

But what is true “freedom”, and how did the Founding Fathers of the U.S. define “freedom,” both in thought and in practice?

As I have previously documented, “freedom and justice for all” did not include many of the inhabitants of the United States during that time, namely all the black slaves “owned” by the Founding Fathers, or the original native Americans who already lived here.

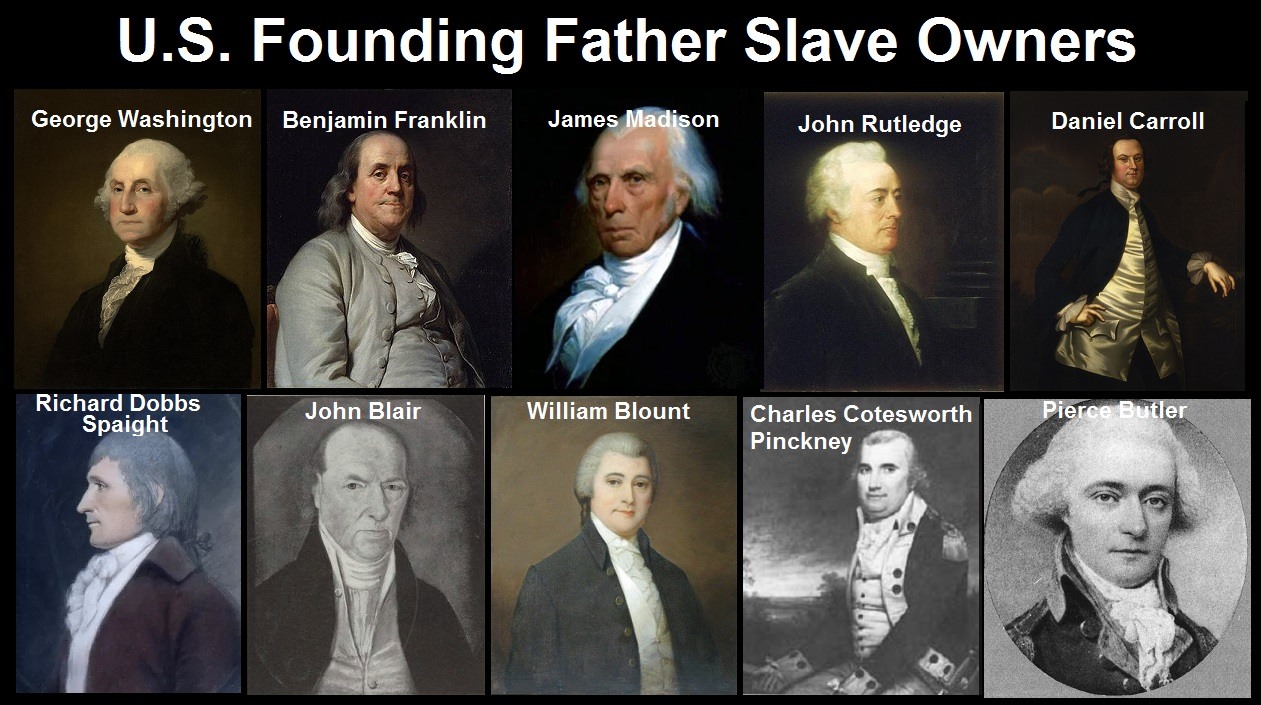

It is estimated that between 17 to 25 of the 55 delegates who signed The Constitution were owners of slaves.

According to the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History, “about 25” delegates enslaved people, of the 55 who attended the convention’s proceedings in Philadelphia.

The Constitutional Rights Foundation asserts that 17 of the 55 delegates were enslavers and together held about 1,400 enslaved people.

In addition to identifying James Madison as an enslaver, Signers of the Constitution, published in 1976 by the National Park Service, notes that 11 other signers “owned or managed slave-operated plantations or large farms,” and then it names them: Richard Bassett, John Blair, William Blount, Pierce Butler, Daniel Carroll, Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer, Charles Pinckney, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Rutledge, Richard Dobbs Spaight, and George Washington.

It is also known that Benjamin Franklin enslaved people. (Source.)

When the European Founding Fathers arrived in North America in the 17th and 18th centuries, they did not find an empty land where there were no people living here.

There was already a system of government in place among several nations that existed in the Northeast called the League of the Iroquois, consisting of at least six North American Indian nations.

This decentralized, agrarian-based form of government in North America went back as far as 1142.

The League of the Iroquois

The Indians of the northeast corridor of North America were not always a peaceful race. In fact, they were perennially at war with one another until, as the Iroquois tradition states, Deganawidah, a Huron from what is now eastern Ontario, proposed the creation of a league of five Indian nations.

He found a spokesperson, Hiawatha, to undertake the arduous task of negotiating with the warring Indian nations.

Hiawatha succeeded in accomplishing Deganawidah’s dream, and the Senecas, Onondagas, Oneidas, Mohawks, and Cayugas ceased their struggle and formed a federal union.

A sixth nation, the Tuscaroras, moved northward from the Carolinas, joining the league around 1714.

Consider the discovery and colonization of America. What confidence could we have in a professor who clung to the pronouncement that Columbus discovered America?

Not much, especially if we already knew that Leif Eric-son, the Vikings, and perhaps even the Phoenicians, Africans, and Jews visited America fifteen hundred years before Columbus arrived.

Barbara Alice Mann and Jerry Fields have more or less established the date 1142 for the Senecas’ approval of the Great Law.

Arthur C. Parker placed the date at 1390 and others, such as Paul A. W. Wallace, at 1450.

Probably by at least 1450—forty-two years before Columbus’s voyage from the decadent Old World—the so-called savages of the New World had formed a federation that would be the envy of Franklin, Jefferson, and Washington.

Cadwallader Colden, a contemporary of Benjamin Franklin’s, wrote that the Iroquois had “outdone the Romans.”

As Bruce Johansen puts it:

Colden was writing of a social and political system so old that the immigrant Europeans knew nothing of its origins—a federal union of five (and later six) Indian nations that had put into practice concepts of popular participation and natural rights that the European savants had thus far only theorized.

The Iroquoian system, expressed through its constitution, “The Great Law of Peace,” rested on assumptions foreign to monarchies of Europe: it regarded leaders as servants of the people, rather than their masters, and made provisions for the leaders’ impeachment for errant behavior.

The Iroquois’ law and custom upheld freedom of expression in political and religious matters, and it forbade the unauthorized entry of homes. It provided for political participation by women and the relatively equitable distribution of wealth. . . .

Nineteenth-and twentieth-century historians supported Cadwallader Colden’s conclusions.

Lewis Henry Morgan, for example, observed in 1851, after a decade of close association with the Iroquois, that their civil policy prevented the concentration of power in the hands of any single individual and inclined rather to the division of power among many equals.

The Iroquois prized individual independence, and their government was set up so as to preserve that independence. The Iroquois confederation contained the “germ of modern parliament, congress and legislature.” (Full article.)

So the term “freedom and justice for all” has always been a lie, ever since the Europeans settled colonized North America, bringing along their African slaves to grow their tobacco on the East Coast, and run their cotton fields in the South, while at the same time destroying the North American Indian nations who are the original inhabitants of North America.

Read More @ HealthImpactNews.com