by David Turver, Daily Sceptic:

The Economist was breathlessly promoting solar power in its recent solstice issue, predicting that “exponential growth of solar power will change the world” and that solar power is going to be so huge that solar energy will become “humankind’s largest source of primary energy – not just electricity – by the 2040s”.

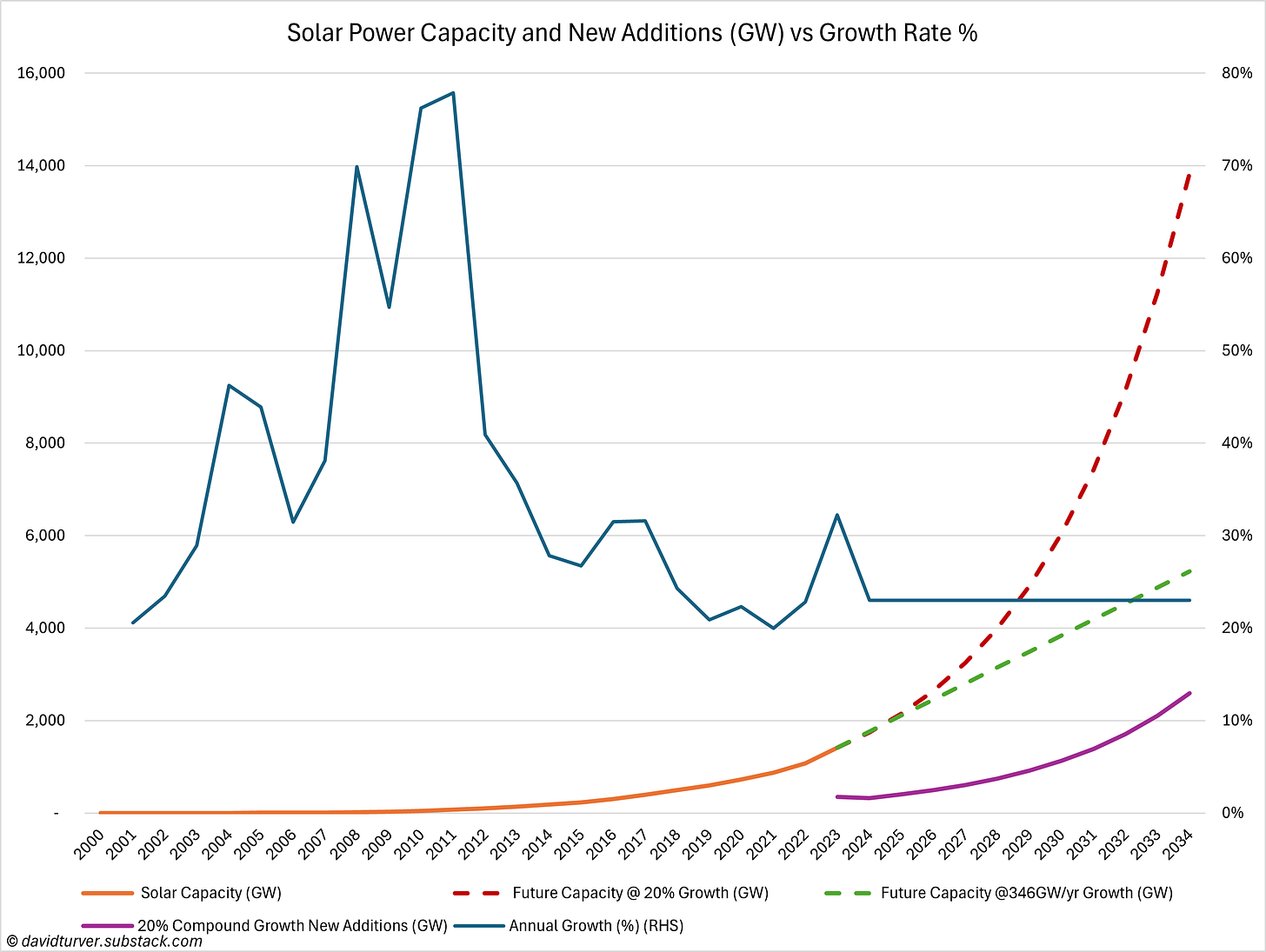

But the Economist is thought by some to be the ultimate contrarian indicator after it famously called the end of the oil age in 2003. As Figure 2 shows, that prediction has not worked out too well.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

How realistic are the Economist’s latest solar power predictions and what might derail their forecasts?

How Fast is Solar Power Growing?

Figure 3 shows, using data from IRENA, how the installed capacity of solar power has increased since 2000 (solid orange line) and the annual growth rate (blue line). The dotted red line shows how installed capacity will evolve if it grows exponentially at the average growth rate for the past five years of 23% per annum. The plum line shows the annual capacity additions at the same 23% growth rate. The dotted green line shows installed capacity if growth is fixed at last year’s rate of 346GW per year.

The wonder of compounding at 23% per year means that by 2032 the annual capacity additions will be larger than the installed capacity in 2023. Let us consider the constraints on that growth.

Cost and Value of Solar Power

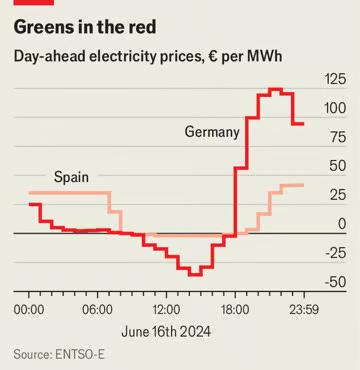

The first thing to consider is the value of solar power generation. Another article in the same issue of the Economist claims that Europe is facing a problem of “ultra-cheap energy”. After I got up from the floor after falling off my chair and stopped laughing, I delved a little deeper to understand why the author had come to that conclusion. It looks like the author has confused market value and cost (see Figure 4).

The Economist’s chart shows that day ahead prices do sometimes go negative on sunny days in Spain and Germany. The market reference price for solar power in the U.K. also reaches extremely low levels on sunny and windy days.

These apparently low prices reflect the market value of the energy generated, not the price we pay in our bills for that electricity. Surely the Economist realises that any enterprise that has to pay its customers to take away its output is not commercially viable. Solar farms can only operate because they rely on generous subsidies. As I have covered before, the latest Feed-in-Tariff report for 2022-23 which is mostly solar shows the average total payment was around £193 per MWh and CfD-funded solar plants currently receive over £110 per MWh. We pick up the difference between low or even negative market prices and the subsidised prices through our bills.

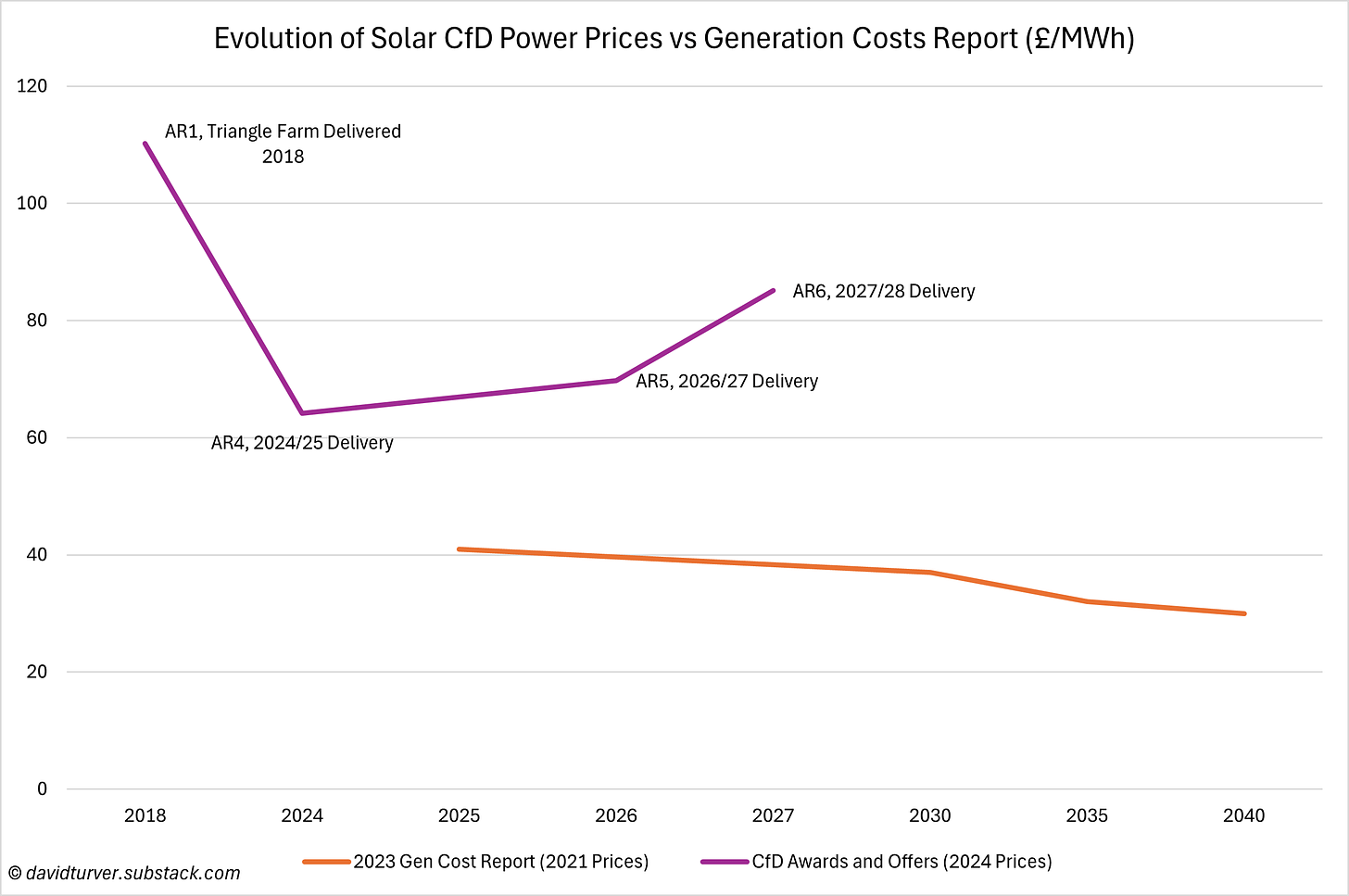

Moreover, despite the Economist claiming and models from Government showing the cost of large-scale solar power falling over the coming years, the prices offered in the various allocation rounds have risen sharply since AR4, see Figure 5.

The gap between the Government model and the strike price they are offering is getting wider and wider. Moreover, recent Government figures show that the installation cost of small-scale solar is rising too and is now above where it was a decade ago in nominal terms, see Figure 6.