by Brian Shilhavy, Health Impact News:

It has been a year and a half now since the first Large Language Model (LLM) AI app was introduced to the public in November of 2022, with the release of Microsoft’s ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI.

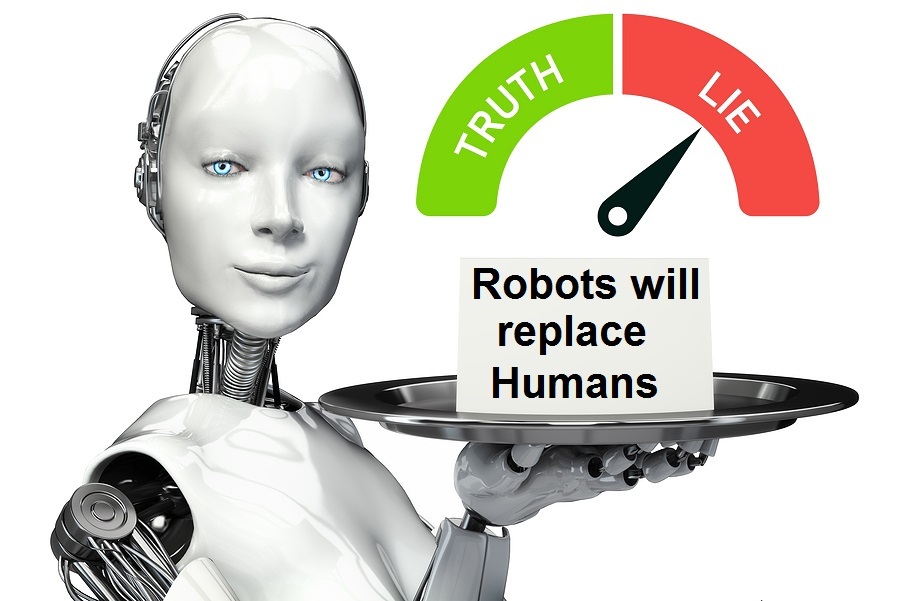

Google, Elon Musk, and many others have also now developed or are in the process of developing their own versions of these AI programs, but after 18 months now, the #1 problem for these LLM AI programs remains the fact that they still lie and make stuff up when asked questions too difficult for them to answer.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

It is called “hallucination” in the tech world, and while there was great hope when Microsoft introduced the first version of this class of AI back in 2022 that it would soon render accurate results, that accuracy remains illusive, as they continue to “hallucinate.”

Here is a report that was just published today, May 6, 2024:

Large Language Model (LLM) adoption is reaching another level in 2024. As Valuates reports, the LLM market was valued at 10.5 Billion USD in 2022 and is anticipated to hit 40.8 Billion USD by 2029, with a staggering Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 21.4%.

Imagine a machine so native to language that it can write poems, translate languages, and answer your questions in captivating detail. LLMs are doing just that, rapidly transforming fields like communication, education, and creative expression. Yet, amidst their brilliance lies a hidden vulnerability, the whisper of hallucination.

These AI models can sometimes invent facts, fabricate stories, or simply get things wrong.

These hallucinations might seem harmless at first glance – a sprinkle of fiction in a poem, a mistranslated phrase. But the consequences can be real, with misleading information, biased outputs, and even eroded trust in technology.

So, it becomes crucial to ask, how can we detect and mitigate these hallucinations, ensuring LLMs speak truth to power, not fantastical fabrications? (Full article.)

Many are beginning to understand this limitation in LLM AI, and are realizing that there are no real solutions to this problem, because it is an inherent limitation of artificial computer-based “intelligence.”

A synonym of the word “artificial” is “fake”, or “not real.” Instead of referring to this kind of computer language as AI, we would probably be more accurate in just calling it FI, Fake Intelligence.

Kyle Wiggers, writing for Tech Crunch, reported on the failures of some of these recent attempts to cure the hallucinations of LLM AI a few days ago.

Why RAG won’t solve generative AI’s hallucination problem

Hallucinations — the lies generative AI models tell, basically — are a big problem for businesses looking to integrate the technology into their operations.

Because models have no real intelligence and are simply predicting words, images, speech, music and other data according to a private schema, they sometimes get it wrong. Very wrong. In a recent piece in The Wall Street Journal, a source recounts an instance where Microsoft’s generative AI invented meeting attendees and implied that conference calls were about subjects that weren’t actually discussed on the call.

As I wrote a while ago, hallucinations may be an unsolvable problem with today’s transformer-based model architectures. (Full article.)

Devin Coldewey, also writing for Tech Crunch, published an excellent piece last month that describes this huge problem of hallucinating inherent in AI LLMs:

The Great Pretender

AI doesn’t know the answer, and it hasn’t learned how to care.

There is a good reason not to trust what today’s AI constructs tell you, and it has nothing to do with the fundamental nature of intelligence or humanity, with Wittgensteinian concepts of language representation, or even disinfo in the dataset.

All that matters is that these systems do not distinguish between something that is correct and something that looks correct.

Once you understand that the AI considers these things more or less interchangeable, everything makes a lot more sense.

Now, I don’t mean to short circuit any of the fascinating and wide-ranging discussions about this happening continually across every form of media and conversation. We have everyone from philosophers and linguists to engineers and hackers to bartenders and firefighters questioning and debating what “intelligence” and “language” truly are, and whether something like ChatGPT possesses them.

This is amazing! And I’ve learned a lot already as some of the smartest people in this space enjoy their moment in the sun, while from the mouths of comparative babes come fresh new perspectives.

But at the same time, it’s a lot to sort through over a beer or coffee when someone asks “what about all this GPT stuff, kind of scary how smart AI is getting, right?” Where do you start — with Aristotle, the mechanical Turk, the perceptron or “Attention is all you need”?

During one of these chats I hit on a simple approach that I’ve found helps people get why these systems can be both really cool and also totally untrustable, while subtracting not at all from their usefulness in some domains and the amazing conversations being had around them. I thought I’d share it in case you find the perspective useful when talking about this with other curious, skeptical people who nevertheless don’t want to hear about vectors or matrices.

There are only three things to understand, which lead to a natural conclusion:

- These models are created by having them observe the relationships between words and sentences and so on in an enormous dataset of text, then build their own internal statistical map of how all these millions and millions of words and concepts are associated and correlated. No one has said, this is a noun, this is a verb, this is a recipe, this is a rhetorical device; but these are things that show up naturally in patterns of usage.

- These models are not specifically taught how to answer questions, in contrast to the familiar software companies like Google and Apple have been calling AI for the last decade. Those are basically Mad Libs with the blanks leading to APIs: Every question is either accounted for or produces a generic response. With large language models the question is just a series of words like any other.

- These models have a fundamental expressive quality of “confidence” in their responses. In a simple example of a cat recognition AI, it would go from 0, meaning completely sure that’s not a cat, to 100, meaning absolutely sure that’s a cat. You can tell it to say “yes, it’s a cat” if it’s at a confidence of 85, or 90, whatever produces your preferred response metric.

So given what we know about how the model works, here’s the crucial question: What is it confident about? It doesn’t know what a cat or a question is, only statistical relationships found between data nodes in a training set. A minor tweak would have the cat detector equally confident the picture showed a cow, or the sky, or a still life painting. The model can’t be confident in its own “knowledge” because it has no way of actually evaluating the content of the data it has been trained on.

Read More @ HealthImpactNews.com