by Daisy Luther, The Organic Prepper:

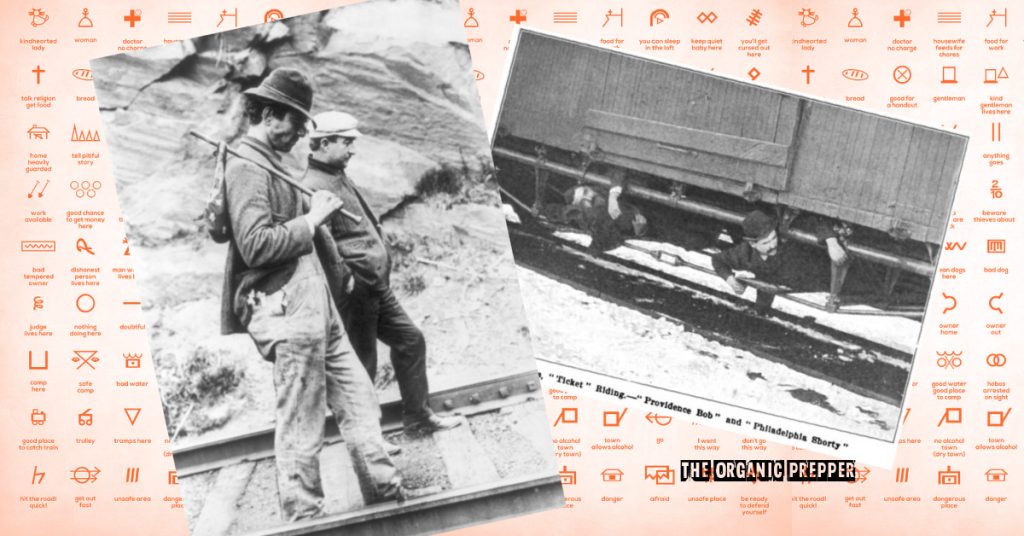

Around 100-150 years ago, the name “hobo” was used to describe a homeless or nomadic person, usually a man, who would hop on freight trains to get from place to place, often to find work. In the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hobos were a well-known subculture, particularly during the Great Depression.

They wandered from town to town, searching for transitory employment, food, and shelter, leading a nomadic lifestyle. Even though they lived on the periphery of society, hobos upheld values that encouraged independence and respect for one another and the community they worked in.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

Hobos were well-known for having a unique culture that included a code of conduct, symbols for communication, and even a yearly convention. The American traveling worker’s folklore has benefited from the songs and stories that hobos frequently wrote about their experiences. Their way of life has also been romanticized in literature, with some seeing it as a symbol of freedom and adventure. There are some interesting things that preppers and survivalists can learn from their lives.

Beyond their cultural and social relevance, hobos are also survivors – a good kind of survivor.

As one can imagine, life as a hobo was challenging and often involved dangers and hardships. However, it was a form of survival for many during a time of economic instability and job scarcity. Hobos didn’t survive on handouts. Instead, they relied on their resourcefulness, the help of their fellow travelers, and the communities they worked in.

In my Street Survival Book, I describe the homeless as “capable survivors.” Regardless of one’s opinion of them – and today, there are many different types of homeless – we must acknowledge the skill set necessary to live on the fringes of society, whether in a city or on the road. It’s something to behold.

Just as with the homeless, there are many different kinds of travelers: hobos, tramps, bums, the Roma, hippies, and so on. Most people consider these types to be connected, but they’re different: a hobo travels and is eager to work; a tramp has a reason to be on the road but tries to avoid employment. And a bum does neither: they stay fixed and rely on the support of others only.

The hobo is subject to the same challenges, hardships, and probations as everyone living on the streets or the road. However, they can be considered unique because of their origins, their history, and, above all, their ethics. Those things make all the difference. Traveling from town to town as a decent person was much easier than a vagrant. Likewise, it’s a lot easier to live in the streets as a decent person.

Also, in my book, I highlighted how decent conduct can impact the standard of living and quality of life of someone living on the streets. After years of trying that lifestyle myself and getting in contact with all kinds of street people, I can affirm that living by the code of the hobo is a superior – much better, safer, and healthier – way than being a bum or worse, an outcast, involved with drugs, alcohol, and crime.

The history of the hobo

Although there are several variations and unclear origins, the name first appeared in the American West around 1890. Some claim it was a shorthand for “homeless boy” or “homeward bound.” Others claim that after the war, Confederate veterans of the Civil War were destitute, impoverished, and hungry, and some even strolled through towns looking for work while carrying a garden hoe. Author and journalist Bill Bryson wrote many nonfiction books on topics in American culture. In his 1998 book “Made In America,” he suggests that the term “hobo” might have originated from the train salutation “Ho, beau!”

By the late 19th century, the heart of Hobohemia was the main drag in Chicago, where train lines radiated out into every corner of America. It was easy to find work in the slaughterhouses, to go west and build a dam, or go east and take a job in a new steel mill to make a buck before you caught the road again.

The hobo would follow the boom-and-bust movements of a shifting economy, searching for transient work like lumbering and mining or seasonal fruit picking in parts of the country without much population, where more hands were needed. That’s how railroads and hobos became integral to the US labor movement, especially in the Pacific Northwest.

The hobo subculture of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries has parallels with the “Beat Generation” of the 1950s. Both embraced alternative lifestyles and values that challenged mainstream norms. The Beat Generation celebrated nonconformity, spontaneity, and a nomadic lifestyle, much like the hobos before them.

Read More @ TheOrganicPrepper.ca