by Pam Martens and Russ Martens, Wall St On Parade:

FRED is a giant online database at the St. Louis Fed that allows anyone to graph the financial and economic data stored in its repositories. We use the data regularly to bring our readers a crystal-clear snapshot of the increasingly dangerous underpinnings of the U.S. financial system.

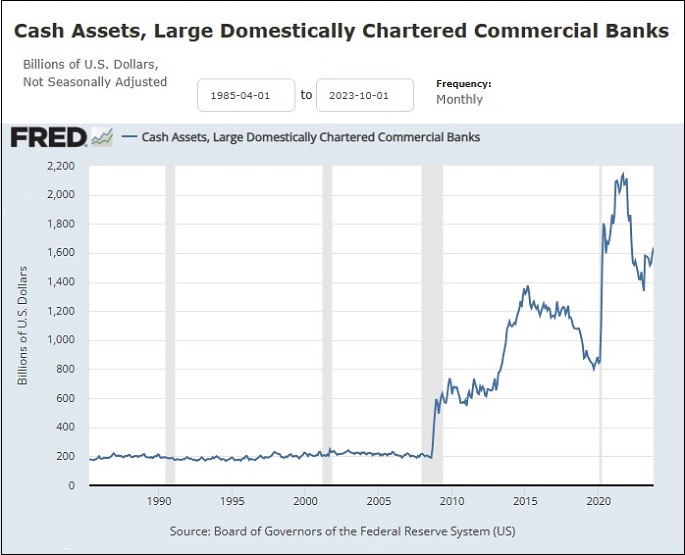

Let’s start with the first chart above. This chart depicts the cash assets held by the 25 largest U.S. commercial banks. The Fed defines the term “cash assets” as “vault cash, cash items in process of collection, balances due from depository institutions, and balances due from Federal Reserve Banks.” Notice that from April 1, 1985 to just before the financial crash of 2008, cash levels at the biggest banks were as steady as a soft breeze on a spring day. But from that point on through today, there have been freakish spikes and plunges in cash levels. Soft-breeze banking has turned into chaotic hurricane banking, with the Fed pumping in trillions of dollars in emergency cash and the mega banks careening from one crisis to the next.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

How did this happen? A brief walk through U.S. banking history is in order.

Following the Wall Street crash in 1929, more than 9,000 banks in the United States failed over the next four years. In just the one year of 1933, more than 4,000 banks closed their doors permanently as a result of insolvency.

The 1930s banking crisis came to a head on March 6, 1933, just one day after President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated. Following a month-long run on the banks, Roosevelt declared a nationwide banking holiday that closed all banks in the United States. On March 9, 1933 Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act which allowed regulators to evaluate each bank before it was permitted to reopen. Thousands of banks were deemed insolvent and permanently closed. There was no federal deposit insurance at that time and it is estimated by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) that depositors lost $1.3 billion to failed banks in that era. That would be approximately $25.5 billion in today’s dollars.

To restore the public’s confidence and encourage Americans to place their savings in bank accounts, Roosevelt signed into law on June 16 the Banking Act of 1933, more popularly known as the Glass-Steagall Act after its authors Senator Carter Glass, a Democrat from Virginia, and House Rep Henry Steagall, a Democrat from Alabama. The legislation created federal deposit insurance for bank accounts for the first time in the U.S. while banning banks that engaged in speculating in stocks or underwriting them to own federally-insured banks.

This separation of banking was greeted with broad public approval at the time. Years of Senate Banking Committee hearings following the ’29 crash had informed the Congress of that era, as well as the public, that Wall Street’s casino banks gambling with depositors’ money in wild stock speculations had caused the stock market crash and ensuing run on the banks.

The Glass-Steagall Act protected the U.S. banking system for 66 years until its repeal during the Bill Clinton presidency in 1999. The impetus for its repeal was the announcement in 1998 that Sandy Weill wanted to merge his trading firms, Salomon Brothers and Smith Barney (under the Travelers Group umbrella), with Citicorp, parent of the federally-insured Citibank commercial bank. (The editorial board of the New York Times was a big cheerleader for letting Weill get his way and for repealing the Glass-Steagall Act.)

Weill had a singular motive for this merger, which created the Frankenbank, Citigroup – and it wasn’t to advance the nation’s interests. Weill told his merger partner, John Reed of Citibank, that his motivation for the deal was: “We could be so rich,” according to Reed in an interview with Bill Moyers.

The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 meant that the casino-style investment banks and trading houses across Wall Street could now own federally-insured commercial banks and use their hundreds of billions of dollars in insured deposits to speculate in stocks and derivatives. Every major Wall Street trading house either bought a federally-insured bank or created one.

What Weill meant by “We could be so rich” was this: If the trading bets won big, the bank CEOs became obscenely rich on stock-option-based performance pay. When the bets lost big, the government would be forced to do a bailout rather than allow a giant, interconnected, federally-insured bank to fail. (You can read about Weill’s Count Dracula stock option/get-rich-quick plan here.)

Read More @ WallStOnParade.com