by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

How do you lose 47% on 30-year Treasuries? Buy at auction in Aug 2020. Or you can carry them at purchase price and hide the “unrealized loss” in the footnotes.

How do you lose 47% on 30-year Treasuries? Buy at auction in Aug 2020. Or you can carry them at purchase price and hide the “unrealized loss” in the footnotes.

“Unrealized losses” on securities triggered the bank panic earlier this year, in that uninsured depositors with millions or billions of dollars at these banks suddenly started looking at the footnote on page 125 of Silicon Valley Bank’s Q4 2022 quarterly report, and saw this thing about “unrealized losses,” and got scared and yanked their money out, electronically, all together in no time, engineering the fastest bank runs in history that took down Silvergate Capital, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic. And this formerly boring line item hidden deep down in the footnotes was transformed into a hotly important indicator of where the entire financial system stands.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

“Unrealized losses” are paper losses on securities that banks hold, but via a quirk in bank regulations, they don’t have to mark them to market value, but can carry them at purchase price.

On one level, it makes sense.

The closer the bonds get to the maturity date, the closer the market value gets to face value, and the unrealized losses vanish, and on the day the bonds mature, the banks get paid face value, and there are no losses, and everyone smiles.

On another level, the bank collapses.

During a bank run, when scared uninsured depositors yank their money out, banks have to sell assets to cover their cash outflows from the run. But now the banks only get market value for those securities – if that, during a fire sale – and not their original purchase price, and they have huge losses on those sales that vaporize their capital. No cash, no capital, no problem? Big problem.

That’s why we now have to pay attention to unrealized losses in the banking system.

Banks can hedge against rising interest rates, but some banks prefer to collapse.

Hedges against the risk of rising interest rates, such as interest-rate swaps, can be costly, and some banks don’t hedge, or don’t hedge enough, because executives prefer to show a little extra income to prop up the banks falling stock price and to fatten up their compensation.

SVB terminated or let expire nearly all its remaining interest-rate hedges in 2022, to where by the end of 2022, they were nearly all gone, and three months later it collapsed.

Where are banks now? Unrealized losses rise by 8% to $558 billion.

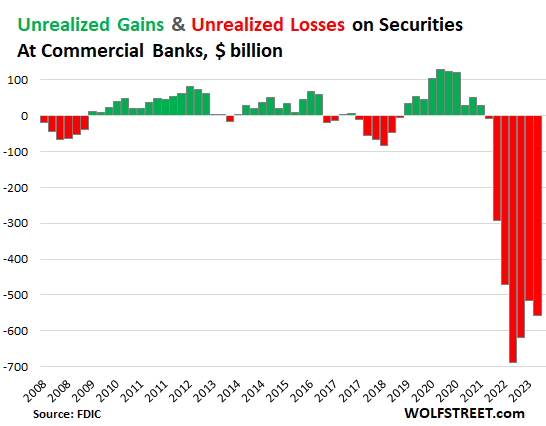

The balance of unrealized losses on securities – mostly Treasury securities and government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities – at FDIC-insured commercial banks rose by $43 billion, or by 8%, to $558 billion in Q2, after two months of declines, according to the FDIC’s bank data on Thursday.

This $558 billion is the cumulative loss balance over time on all securities. The balance rose because longer-term yields rose in Q2: The 10-year Treasury yield rose to 3.84% on June 30, from 3.47% on March 31, and so bond prices fell over the period.

In the free-money periods, when yields fell and bond prices rose, banks had “unrealized gains” (green). And in the periods when yields rose and prices fell, banks had “unrealized losses” (red).

These unrealized losses of $558 billion were spread over two categories of bank accounting treatments:

- Unrealized losses on held-to-maturity (HTM) securities: $309.6 billion

- Unrealized losses on available-for-sale (AFS) securities: $248.9 billion.

The balance of unrealized losses is down by $131 billion from the peak in Q3 2022, in part because three banks with big unrealized losses collapsed, and their balance sheets vanished from the system, with losses getting transferred to the FDIC.

Already gotten worse in Q3 so far.

Thing is, today, the 10-year yield closed at 4.27%, and if it’s still at 4.27% at the end of September, it would be another 43 basis points higher than at the end of Q2, and the balance of unrealized losses will be higher yet again.

Bad-case scenarios: How big can the losses be on specific bonds?

A bank that bought $1 million of 10-year T-notes at the Treasury auction on August 12, 2020, at the very tippy-top of the 40-year bond bull market, ended up with a security that paid a coupon interest rate of 0.625% per year. Today, this security has seven more years to run before maturity, and so trades like a 7-year Treasury security, and the 7-year yield today in the market is 4.35%.

So how much is a security worth today with a coupon of 0.625% per year and with seven years to maturity, when the equivalent market yield is 4.35%?

Roughly, that $1,000,000 in 10-year T-notes might be worth $778,000 in the market today – thank you, bond-price calculator. Results may vary.

The bank that purchased this security at auction and carries it under HTM accounting rules on its books would show no loss on its income statement, and its earnings-per-share would be just fine, and it would pay its executives big-fat bonuses.

But on its balance sheet way down somewhere in the footnotes, it would show an “unrealized loss” of roughly $222,000, or roughly 22.2% of the purchase price.

And that $1,000,000 in 30-year T-bonds that a hapless bank bought at auction in August 2022, with a coupon of 1.375% might sell for about $529,000 today, for a loss of about $471,000, or 47%. That’s about the worst-case scenario, the punishment for buying at the peak of the 40-year bond bull market.