by Harley Schlanger, LaRouche Organization:

Oct. 28—A headline in Newsweek’s October 20 issue should have triggered profound anxiety among those who remember events of 60 years ago, when many feared that the United States and the Soviet Union were headed toward a nuclear war over Soviet missiles placed in Cuba. The headline read “Russian Envoy to U.S.: Channel That Stopped Nuclear War 60 Years Ago Is Dead.” It referred to comments made by Anatoly Antonov, Russia’s current Ambassador to the United States.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

As loose talk of a possible nuclear war is heard daily, especially from NATO officials and their media mouthpieces who endlessly repeat the false charge that Russia’s President Vladimir Putin threatened to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, Antonov warned that “the infrastructure of our communication with America has been demolished.” To highlight the heightened danger resulting from this, Antonov referred to comments made by the Russian Ambassador to the United States at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Anatoly Dobrynin, who said:

“The Cuban missile crisis revealed the mortal danger of a direct armed confrontation of the two great powers, a confrontation headed off on the brink of war thanks to both sides’ timely and agonizing realization of the disastrous consequences.”

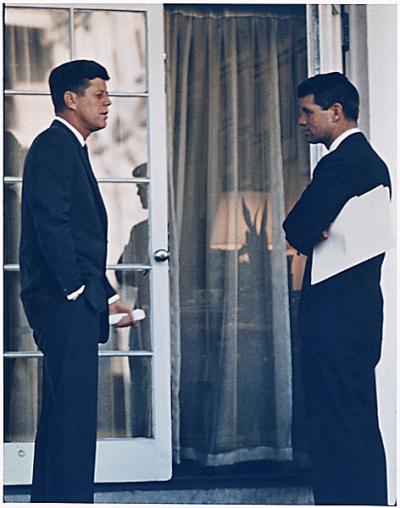

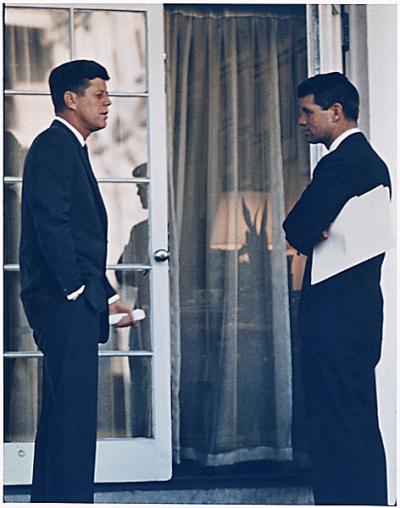

Dobrynin had played a decisive role in defusing the crisis in October 1962, through backchannel discussions with President Kennedy’s special envoy, his brother Robert (RFK). This channel enabled John Kennedy (JFK) to communicate with Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev through a trusted intermediary, and ultimately led to a peaceful resolution of the conflict. The direct message being sent by Antonov to U.S. officials is that one of the main lessons—which should have been internalized by officials today—is that the absence of such infrastructure today increases the danger of miscalculation, or an accident, which could trigger an all-out nuclear war.

1962—Prelude to Dialogue

When JFK was first briefed by his National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy on October 16, 1962 that the CIA believed that the Soviets were installing medium- and intermediate-range missiles in Cuba, he set up an Executive Committee (ExComm) to formulate a response. Made up of civilian members of the National Security Council, intelligence officials, and members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, its initial recommendations were to hit the missile sites and/or to invade Cuba.

For Kennedy, the discovery of the missiles represented not just a military crisis, but a political one. He had campaigned for the presidency demanding a tough stance toward Cuba, and had agreed to go ahead with the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961, just three months after his inauguration—though it had been organized by the previous administration, and he feared it had little hope of succeeding. When it failed, he was criticized for being “weak” for not backing up the bungled effort with a military invasion. The fiasco of the Bay of Pigs was quickly followed by a Berlin crisis, culminating in the division of the city by the construction of a wall in August.

According to tapes made of the ExComm sessions, JFK’s immediate reaction to the discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba was to state that it was “politically unacceptable” to allow them to remain. Virtually every member of ExComm advocated a harsh military response. Among the hard-liners were Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, Bundy, elder statesman Dean Acheson, and the military brass. Numerous accounts, based on documents and tapes declassified in the late 1980s, report that it was the nearly unanimous view of his advisers that they must respond forcefully to demonstrate that Washington would honor its commitments; that is, that America would not adopt an “appeasement strategy” to avoid nuclear war with the USSR.

Instead of striking the bases in Cuba, JFK chose to enact a blockade, or “quarantine” of Cuba, to prevent more missiles and weapons from reaching the island nation. He announced this in a national televised address on October 22, despite intense pressure to go to war. One member of the committee, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Curtis LeMay, spoke for the war hawks, saying the blockade is “almost as bad as the appeasement [of Hitler] at Munich.” LeMay and his allies were prepared to risk a nuclear war to show that Khrushchev could not push the United States around.

The Backchannel

Although stopping Soviet ships at sea was risky, JFK saw it as a way to buy time for diplomacy. According to RFK’s memoirs, JFK chose to allow the first tanker encountered by the U.S. naval blockade, the Bucharest, to pass through, saying, “We don’t want to push him (Khrushchev) into a precipitous action—give him more time to consider. I don’t want to push him into a corner from which he cannot escape.”

It was at this point that RFK entered into a dialogue with Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin.

On October 27, after five days of excruciating tension, Khrushchev made a proposal that ultimately led to a peaceful resolution: He offered to withdraw the missiles in return for a pledge that the United States would not invade Cuba or overthrow Castro, and would remove Jupiter nuclear missiles then stationed in Turkey. While the American hardliners opposed the trade, ridiculing it as “appeasement,” JFK agreed to it, but insisted that the withdrawal of U.S. missiles not be made public. What was said publicly, was that Kennedy refused the offer to withdraw the missiles from Turkey, spinning the deal as a unilateral retreat by Khrushchev. On Oct. 28, the Soviets began to dismantle the missile bases in Cuba.

Read More @ LaRoucheOrganization.com