by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

It’s already playing a key role in every one of Powell’s press conferences.

It’s already playing a key role in every one of Powell’s press conferences.

Just about every day, there are stories of layoffs, but mostly small-scale layoffs, in the hundreds, 300 people here, 500 people there – of the 153 million employed people. Occasionally, there were layoffs of 1,000 or 2,000 people, and sometimes those are in global operations, with an unknown number in the US. Then there are large companies that are laying off staff in the divisions they’re trimming back, but they’re hiring in their other divisions, and often employees can get hired by another division.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

And they just don’t add up to the mass layoffs in the prior recessions, where big companies would make serial announcements of layoffs of 10,000 or 20,000 people at a time per company. In addition, there are massive well-documented staff shortages in some sectors, such as schools (the “teacher shortage”), in healthcare, and others.

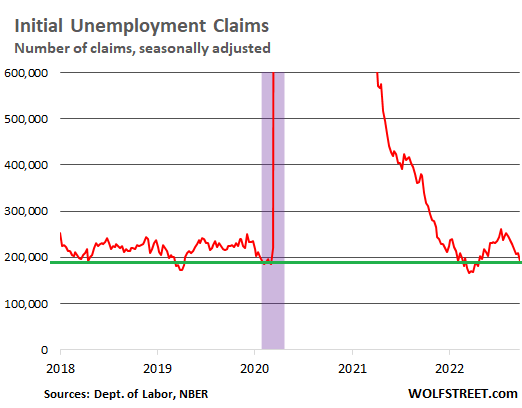

And we’re seeing that in the initial claims for unemployment insurance. For the week ended September 24, released today by the US Department of Labor, the initial claims for unemployment insurance fell by 16,000 from the prior week to 193,000 (seasonally adjusted) – near historic lows. This shows that most of the people who are being laid off either already had a new job lined up when they walked out the door, or they’re finding a new job very quickly, before even filing for unemployment insurance: another sign of how strong the labor market still is:

These weekly “initial unemployment claims” are not based on surveys, as other labor market data is, but on actual claims for unemployment compensation, filed by people who’ve lost their job and haven’t found another job yet, and who want to be paid unemployment benefits to tide them over.

Initial unemployment claims are the most immediate measure of the labor market, and they just refuse to show any weakness.

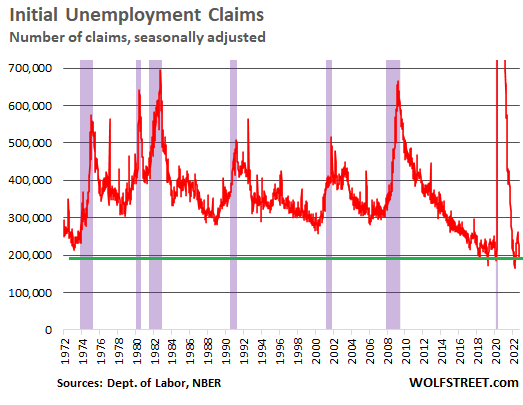

Over the decades, significant and lasting spikes in initial unemployment claims were associated with recessions, and every recession was preceded by them.

Going back to the recessions through 1974, including the nasty “double-dip” recessions in the early 1980s, we can see how today’s initial claims for unemployment insurance still depict a strong labor market.

Before and during recessions, these initial claims for unemployment insurance surge because people who lost their jobs cannot find another job quickly because other companies too have stopped hiring or have started laying off people. This would be a sign in the data that the labor market has started to run into serious trouble. But not yet (purple areas indicate recessions, recession dates from NBER).

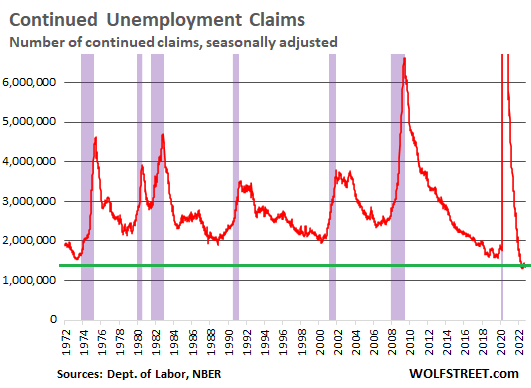

The number of people that continued to claim unemployment insurance in the week following the “initial” claim – the “insured unemployment” – fell by 29,000 from the prior week, to 1.347 million, just a hair above the record lows earlier this year and far below the levels of any other healthy labor market, and far far below recessionary levels – another sign of just how strong this labor market still is, and how powerful the labor shortages still are in absorbing people that have gotten laid off:

This confirms other labor market data: Still huge demand for labor and tight supply.

Large-scale surveys of employers have shown that all year through July, the latest month reported, the number of employees who were laid off or discharged has remained near record lows; and the number of job openings, at over 11 million, has remained in the astronomical zone, up by 61% from the same period in 2019; and employees are still quitting jobs in historically large numbers, a sign of massive churn and job hopping as they take advantage of still strong demand for labor to obtain a better job, more pay, or better working conditions.

The labor force is still not back where it had been before the recession – and that is part of the problem with the labor market. Very strong demand for labor meets very tight supply. The result is rising wages – and in terms of just wage increases, this has been the best labor market for workers in decades.

The problem is that inflation is red hot, and is outrunning even those wage increases, and those wage increases provide further fuel for inflation – and here we go: the wage-price spiral.