from RT:

The US Central Intelligence Agency recently turned 75. I have my reasons to wish it doesn’t see another birthday

The US Central Intelligence Agency recently turned 75. I have my reasons to wish it doesn’t see another birthday

My initial introduction to the CIA was through the medium of film and literature. The spy versus spy mystique was alluringly romantic, with a definite ‘good versus evil’ vibe. I grew up, after all, during the Cold War, where the ‘red menace’ permeated every fiber of American popular culture.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

I opted to serve my country in the military, and not as a spy, receiving a commission in the Marine Corps in 1984 as an intelligence officer. My specialty was combat, not espionage, and it seemed that my path and that of the premier American intelligence agency were never to cross.

In 1987, the US and the Soviet Union signed the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, which included as part of its compliance verification scheme on-site inspections. I was selected to serve in the On-Site Inspection Agency (OSIA), a Department of Defense activity tasked with implementing the on-site inspection provisions of the INF treaty.

The intelligence aspects of monitoring overall Soviet compliance with the INF treaty were overseen by an entity known as the Arms Control Intelligence Staff, or ACIS, which reported directly to the Director, CIA. Early on in my tenure as an inspector, I established a relationship with ACIS that was linked to the unique role I played as an inspector on the ground in the Soviet Union. Over the course of two years, I was twice recognized by the CIA in classified commendations for my work in Votkinsk. The first commendation was from the director of the CIA at the time, William Webster. The second was from the head of the Treaty Monitoring Management Office within ACIS, John Bird.

I detail my relationship with the CIA during this time in my book, ‘Disarmament in the time of Perestroika: Arms Control and the End of the Soviet Union’ (published by Clarity Press.) At the time, I viewed the CIA as a collection of professionals who effectively and diligently carried out their mission of verifying Soviet compliance with the INF treaty.

Near the end of my tour with OSIA, I was summoned by John Bird to his office in the agency’s Langley, Virginia, headquarters, where he offered me a job with the CIA. It was a very good offer, but one which I turned down. I was a Marine Corps officer, and it was time for me to return to the Fleet Marine Force.

Shortly after I left OSIA, Iraq invaded Kuwait, setting in motion events which culminated in Operation Desert Storm, the US-led war against Iraq. I was assigned to the headquarters of US Central Command, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where I played a role in what became known as the ‘Great SCUD Hunt’ – the coalition effort to locate and destroy Iraqi SCUD missile launchers before they could fire on targets in Israel and the Arabian Peninsula.

During this time, I was introduced to a unit known as the Joint Intelligence Liaison Element, or JILES, a CIA team attached directly to Central Command. I had occasion to work with them on a few projects and found them to be very professional and approachable.

So far, so good.

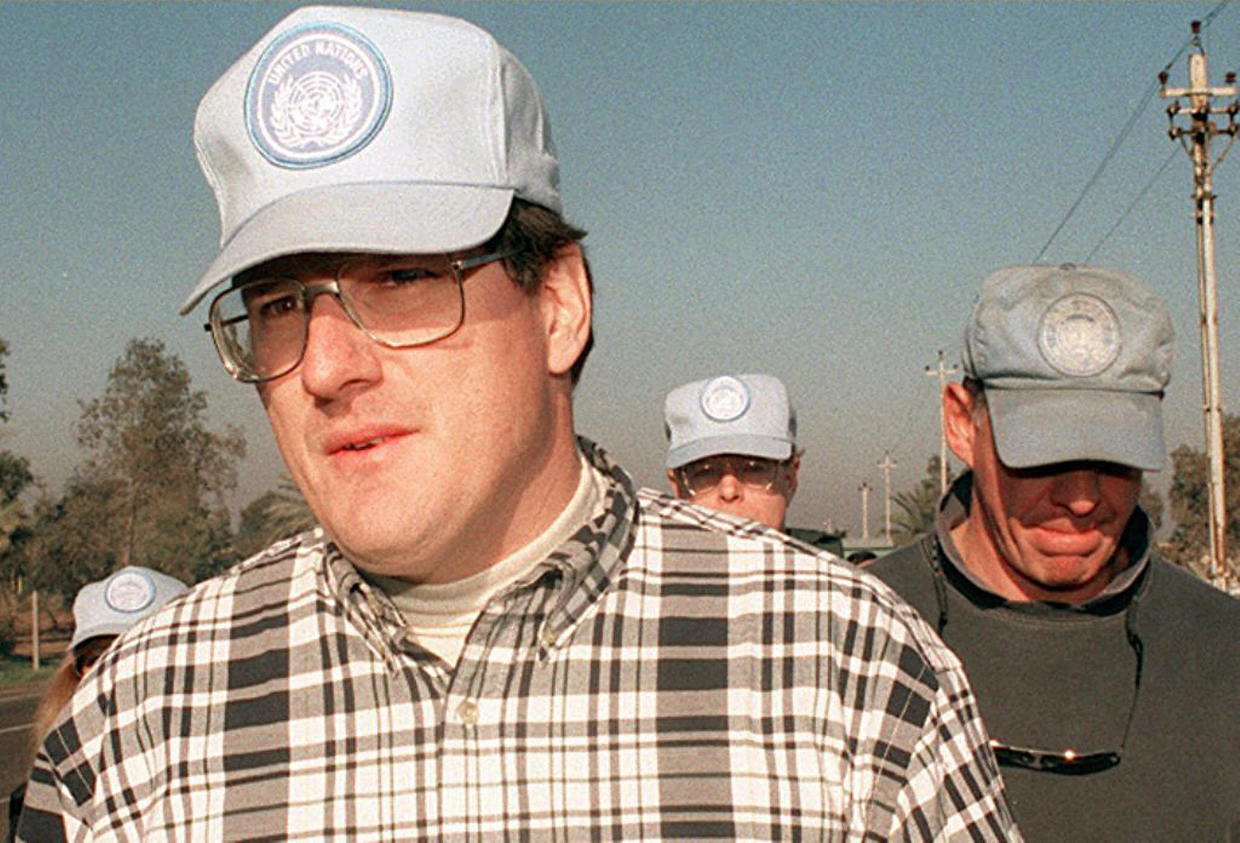

After the war, I left the Marines, and was soon thereafter recruited by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), created after the war to oversee the elimination of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.

Shortly after I arrived at the UN headquarters, I once again found myself working with the CIA. John Bird and ACIS had formed a new entity, the Iraqi Sanctions Monitoring Office, or ISMO, which had assumed responsibility for providing intelligence support to UNSCOM. Inspections are an intelligence-directed activity (i.e., the intelligence community provides information about the potential targets to be visited by inspectors) and given my task of overseeing the creation of an intelligence capability within UNSCOM (known as the Information Assessment Unit, or IAU), I found myself frequently interfacing with my old colleagues.

Only this time it was different. Not only was I no longer on the inside, so to speak, but it turned out that my marriage to Marina Khatiashvili, a Georgian national who I became acquainted with during my time as an inspector with OSIA, and who I courted and married after leaving the Marine Corps, had infuriated John Bird, who had apparently been taken to task for trying to recruit a guy (me) who then went off and married a Soviet.

I didn’t matter that I had broken no rules or laws, or that the Cold War was over. For John Bird, this was personal.

By the spring of 1992, the tension between UNSCOM and the CIA over my continued role (I had by this time taken over the ballistic missile account and was heavily involved in planning and implementing inspections in Iraq) led the CIA to confront me directly. The agency dispatched Stu Cohen, a senior officer with experience in arms control, to meet with me.

Stu indicated that the CIA believed it could no longer provide intelligence support to UNSCOM so long as I was part of the team. He stated that the CIA believed that my marriage had compromised me.

I told Stu my marriage was literally none of the CIA’s business, and that I had never done anything that violated my oath of allegiance to my country.

A compromise was reached where I gave Stu permission to conduct a thorough investigation into my work with OSIA and my marriage to Marina. If the CIA uncovered anything untoward, I would quietly resign from UNSCOM. However, if the CIA found nothing, then I would remain at UNSCOM, and the CIA would continue to provide unfettered intelligence support.

A few months later Stu returned. The investigation was complete. Stu had uncovered a memorandum, written by John Bird, which stipulated that I was a “known threat” to the United States, and should be treated as a serious security risk. This letter was the Genesis of all CIA concerns. Stu had tracked Bird down in Geneva, Switzerland, where he was participating in arms control negotiations with the Russians.

After a detailed questioning, Bird admitted that he had no evidence that I had done anything wrong, but that he personally took exception to my marriage to Marina and wrote the memorandum out of spite.

Stu kept his word, and for the next six years I was able to carry out my disarmament mission, all the while being supported by the CIA, which coordinated with me on the most sensitive human, technical, and imagery intelligence matters.

However, I was shocked at the way a senior CIA official could seemingly abuse his position to try and ruin the life of an American citizen simply because he took personal umbrage over something that had nothing to do with his official duties.

As my work with UNSCOM expanded, so, too, did my interaction with the CIA. After a series of difficult inspections, where my performance was singled out by the US intelligence community, I was approached by a senior CIA officer who encouraged me to apply for a position within the agency.

At this juncture, I was very conflicted about my work with UNSCOM. As an American, my loyalty has always been to my country first and foremost. Shortly after I joined UNSCOM, I traveled to Washington, DC, where I met with the interagency team, drawn from the State Department, the CIA, and the Department of Defense, that oversaw support to the UN inspectors. I asked them to clarify my chain of command – did I work for the UN, or did I take my orders from the US government?

I was told in no uncertain terms that my job was to implement Security Council resolutions as directed by the UNSCOM executive chairman, a Swedish diplomat named Rolf Ekeus.

I proceeded to do just that, only to find that there was tension between UNSCOM and the US over a US-specific agenda regarding Iraq which seemed to support regime change in Iraq over disarmament of Iraqi WMDs.

I was often at the center of this tension, being pulled in two directions. I always fell back on my instructions to faithfully execute the orders given to me by the UNSCOM chairman. This did not, however, assuage the sense of guilt that accrues when one is no longer viewed as being ‘part of the team’, especially when talking about ‘Team USA’.

I applied to the CIA, hoping to land a position as an analyst in the former Soviet Affairs division, now renamed the Office of Russian and East European Affairs. I was invited down to Langley, where I interviewed with a senior manager. The long and short of it was, my application was rejected because I was considered too ‘old school’ in my thinking. “It’s not the Cold War,” the manager told me. “We need people who can look at the Russian problem with a fresh perspective.”

Apparently, my commendations from the director of the CIA, all based upon analytical work, were not seen as an asset anymore.

There was another part of the CIA, however, which began taking a greater interest in my work. Known as the Directorate of Operations, or DO, this aspect of the CIA did not deal with analysis, but rather the murky world of human intelligence and covert activity. As the work of UNSCOM transitioned away from the task of accounting for the WMDs declared by Iraq, to searching for evidence of WMDs that Iraq was hiding from the inspectors, so, too, did the nature of the inspections themselves.

I was at the center of this transition, taking the lead in organizing and leading extremely aggressive, confrontational inspections designed to uncover hidden aspects of Iraq’s undeclared WMD arsenal. I headed up an international intelligence effort which included the intelligence services of several nations, including the CIA. We made use of the entire spectrum of intelligence capabilities to fulfil the mandate of disarmament set by the Security Council.

After one particularly difficult and high-profile inspection, which made use of ground penetrating radar developed in conjunction with the CIA, I was approached by a senior officer from the Special Activities Division – the paramilitary branch of the CIA, responsible for covert action around the world. “The agency would like to have you onboard,” he said, “but your profile is too high. Go back to the Marines, lay low for a couple of years, and then reapply. We will be waiting for you.”

By the spring of 1994, UNSCOM was transitioning into long-term monitoring operations, and my skill set – hunting for hidden weapons – was no longer seen as necessary. So, I returned to the Marine Corps, and did my best to disappear into obscurity.

It wasn’t meant to be. Within a few months of my new assignment, I was visited by a CIA team, who briefed me on growing concerns that Iraq was hiding weapons and seeking my advice on how they should go about organizing to uncover evidence of their existence.

By September 1994, I was back in New York, on temporary assignment to UNSCOM, where I began preparations for a new phase of operations. Back in 1993, I had approached the CIA for help in deploying a covert signals intelligence capability, under UNSCOM control, to Iraq to intercept Iraqi radio traffic related to the hiding of WMD. At that time, the CIA balked, unwilling to cede control of such a sensitive resource to an international organization.

I proposed that UNSCOM approach Israel for this assistance, and the CIA agreed. I made two trips to Israel, where eventually a deal was struck that had me working with Israeli photographic interpreters to analyze imagery from UNSCOM-controlled U-2 reconnaissance aircraft. Using this imagery, I would gain access to real-time Israeli intelligence which could be used to direct the work of the inspectors. The British agreed to provide a signals collection team, and the product would be jointly assessed by the US, the British, and Israel.

This arrangement was agreed to at a meeting, held at the Princeton Club in downtown New York, between the new senior CIA liaison for UNSCOM, Larry Sanchez, Rolf Ekeus, his American deputy, Charles Duelfer, a senior UNSCOM inspector named Nikita Smidovich, and me.

The Marine Corps, however, would not agree to release me for an extended period, and so once again I left the Marines, and returned to UNSCOM, this time under a complicated employment vehicle in which the CIA funneled money to OSIA, which then paid me per a contract that would be renewed every six months.

This relationship led to a renewed campaign of extremely aggressive inspections which touched on the most sensitive aspects of Iraqi security, including the president of Iraq himself. UNSCOM believed (rightly so) that presidential security was involved in the hiding of WMDs from the inspectors.

What we didn’t know is that the CIA was using the UNSCOM inspections – especially the communications intercepts, which were focused on presidential security – to implement a covert operation designed to remove Saddam Hussein from power. This plan was implemented in June 1996, while a team I was leading was involved in a stand-off with the Iraqi authorities regarding access to sites affiliated with the Iraqi presidency.

The CIA had used my team to trigger a crisis which was supposed to end with US cruise missiles taking out Iraqi security forces, while a unit from the presidential security guards that had been recruited by the CIA assassinated Saddam Hussein and replaced him with a hand-picked CIA asset. The coup plot failed spectacularly, humiliating the CIA, which in turn went searching for someone to blame.

That someone was me.

I knew absolutely nothing about the planned coup. I had, however, been engaged in the debriefing of Iraqi defectors who were under the protection of the Jordanian intelligence service. I learned later that these defectors were simultaneously working with the CIA in support of the coup effort. I was seeking to get information about how they hid WMDs from UNSCOM; the CIA was seeking information about how they protected the Iraqi president.

The CIA’s Directorate of Operations put the blame on me, alleging that I had tipped off Iraq about the information I had learned by debriefing the Iraqi defectors.

Tired of portraying me as a Russian spy, I was now painted as spying for Iraq.